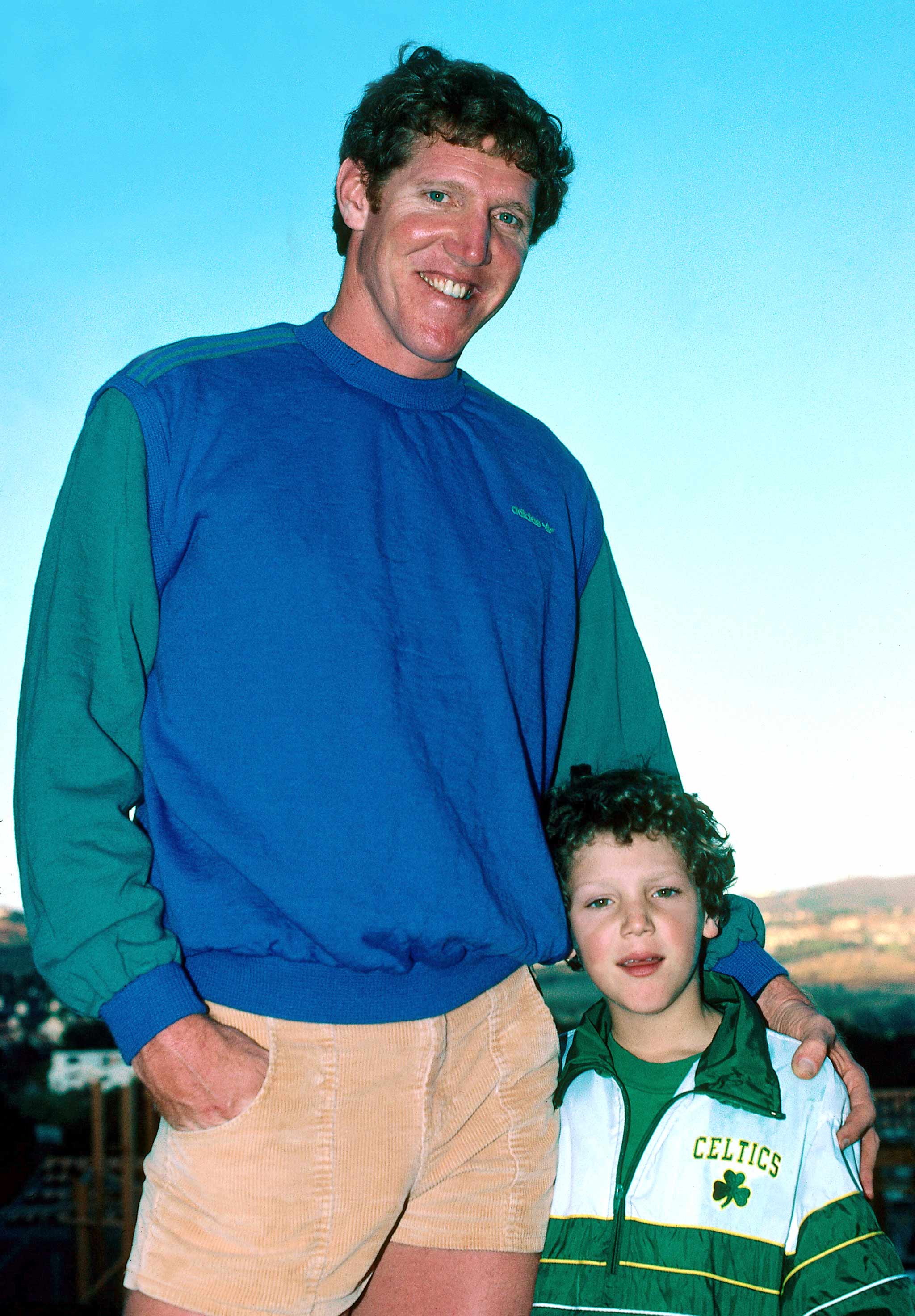

Luke Walton (left) stands next to his father, Bill, before Game 5 of the 2008 NBA Finals between the Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics at Staples Center on June 15, 2008 in Los Angeles. (Getty Images)

Let's catch up a little: The coach and I are at a ritzy Sacramento restaurant a day after the presidential election. One-on-one. Luke strides in wearing a hoodie and sweats. His team is 4-4, but there is excitement that, at the very least, he will make the Lakers interesting again. Russell and fellow franchise player, Julius Randle, are showing flashes of superstardom, and even Nick Young, the much-maligned journeyman, is flourishing.

In this city that was once enemy territory, Kings fans from all over the restaurant come up to Luke throughout the meal and wish him good luck, or else just pat him on the shoulder. He smiles back and shakes hands. He is 14 days into the season.

When a large group starts pounding shots at the bar, a waitress comes over and remarks how "lively" our fellow diners have become. "You know why they're celebrating," Luke smirks, rolling his eyes.

But he doesn't want to talk politics. When Luke tells stories of his playing career, he leans forward, and his voice booms: "My rookie year, we were headed to Hawaii," he begins. After an All-American career at Arizona, the Lakers drafted him onto a loaded team in 2003 that featured Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O'Neal, Gary Payton and Malone. "They all hated my dad for one reason or another. I'm sure he had said something about all of them. They said they were going to make my life hell."

On the flight over the Pacific, "they had an auction to see whose rookie I'd be," Walton said. "Karl Malone played $20,000 in the pot, so I was his personal rookie. Anything he wanted I was going to have to do."

But it didn't last. Malone eased up when he saw how unselfish Luke was on the court. "We got along so well. I did everything he asked," Luke says. "He was like, 'Look, we're not going to take out our feelings of your dad on you.'"

Luke's main problem was that he was too analytical; he has always cared a little too much. After losses, even during the preseason of that rookie year, he'd sit in the back of the team bus or plane with a knot in his gut: "I felt like I didn't deserve to be happy." His teammates tried to explain the NBA schedule—We play 82 games, so you'd better get OK with losing—but it did little good.

Phil Jackson talks with Luke Walton during a game against the Clippers at Staples Center in Los Angeles. (Getty Images)

He coped through impromptu meditation classes with Jackson, the Zen Master himself. "Phil would pull his chair up to the front, and he'd talk us through it: Breathe. You're a frog. You're on a lily pad." Luke would open his eyes and look around the film room, assuming it was a prank. "Then you realize it's not; then you do it." Even today, when the Lakers struggle, Luke will find a quiet room in his house and imagine Jackson leading him from one lily pad to the next.

Luke soon became one of Jackson's top pupils, learning about the interconnectedness of the game. "My mind opened up," he says. "If the first pass of the offense was a shitty pass at someone's leg, that's how the chain reaction kicked in. If we didn't correct it then, then it snowballed." By the time he was an integral member of Jackson's rotation, he came to see the triangle offense as "a beautiful thing."

The Lakers won back-to-back championships in 2009 and 2010, but during the second title run Luke was dogged by injuries and played only 29 games. Jackson noticed how distant he had become and brought him into his office. Jackson had gotten his coaching start under similar circumstances when he was hobbled while playing for the Knicks, and he soon asked Luke to sit in during staff meetings and give his thoughts. "He told me one day if I wanted to get into coaching, 'You're going to be good at it,'" Luke says.

Jackson also gave his pupil one crucial piece of advice: If you're going to be a good coach, there are times you have to be an asshole—even if you don't want to be an asshole.

✦ ✦ ✦

It is the great irony of the rapid ascent of the head coach of one of the most storied franchises in sports that, two-and-a-half years ago, Luke Walton didn't think he wanted to be a coach at all. He had retired from the NBA after a forgettable season with the LeBron-less Cavs in 2012-2013—coached by Byron Scott—and for months, he says, "I was just trying to find direction in my life." In the mornings he worked out with a trainer, then he played beach volleyball, followed by yoga.

He tried to get back into basketball, working as a broadcaster on local Lakers telecasts and part-time as an assistant coach for the 2013-14 Lakers D-League team, but he found it hard to get his team-centric message across. "Everyone would tell me, 'If I don't score 35 a night, I'm not getting out of the D-league.' They're kind of right," he says. "It just didn't have the same level of satisfaction."

Feeling lost, Luke called an old friend who was working with the Warriors as Kerr was taking over the head coaching job. Luke wanted to get back in the gym and asked his friend if he knew any new drills. At the end of the conversation, Luke hesitated. Hey, does Steve have any staff up there yet? His friend told him there was, indeed, one opening, and Luke took the bait, albeit awkwardly: So, umm, how would it work? Should I send him a resume?

Kerr, intrigued, spoke to Luke the next day but wanted to know more about his basketball philosophy, which Luke hadn't really thought about since back in the John Wooden-on-his-lunch bag days. He rambled through some old advice from Olson and Jackson, and then, when he got past the triangle to the part about the precision of offensive spacing, Kerr perked up: The job is yours if you want it.

"They had an auction to see whose rookie I'd be. Karl Malone played $20,000 in the pot, so I was his personal rookie. Anything he wanted I was going to have to do."

When Luke showed up at Warriors training camp that summer of 2014, he was surprised to find Kerr praising his new players instead of asserting his authority: We're lucky to coach you.

"I thought it was simple but brilliant," Luke says. "Most coaches would come in right away and mark their territory and show who the boss is. Steve took the exact opposite approach."

In the Warriors, he found another footloose and, yes, privileged family; in Kerr, a kindred spirit. "It's one of the best bromances I've ever seen," Susie Walton says. Following Kerr's back surgeries before last season, Luke was appointed interim coach and led the Warriors to the second-best start in NBA history at 39-4, but the old guard still grumbled: Was this the next great NBA coach, or just the product of a brilliant system?

✦ ✦ ✦

Let's get down to business: Philips Arena, fifth game of the season. Tough times for the purple and gold—three L's in a row, marking Luke's longest losing streak in his two-plus-year career as a coach. Lakers up four, less than a minute to go. The Hawks' Dennis Schroder pounds the ball at the top of the arc, as his teammate Paul Millsap races up the key to set a screen. In this moment, the Lakers defenders have a game-defining decision to make.

During the preseason, with five players under 24 years of age, Luke's assistant coaches pushed for a regimented defensive structure. "I'd say, 'Let's do it one way every single time,'" Mermuys recalls. "'Then do it over and over again, then by the end of the season, we'll be a solid defensive team.'"

Luke saw that as a short-term view. His team would learn pick-and-roll defense but wouldn't develop basic critical-thinking skills. "If you put too many rules on it," Luke would say, "then they can play like robots."

Before that last defensive stand against the Hawks, Luke didn't give his players specific direction on how to defend the pick-and-roll. Instead, he told them to read the action—whatever it was. Randle switched onto Schroder, shadowed him to the hoop and blocked his layup off the backboard, sealing win No. 2.

Luke Walton complains to referee Bennie Adams about a call during a game against the Clippers at Staples Center on Dec. 25, 2016 in Los Angeles. (Getty Images)

"That was all Luke, staying true to himself," Mermuys says. It was a seminal moment for the team and its coach, and when I met Luke in Sacramento, the Lakers were fast becoming the darlings of the NBA. "I haven't had to be an asshole yet," he told me.

Then, within six weeks, the wheels fell off and the Lakers lost eight in a row—the kind of skid that can transform even the coolest coaches into the raging control freaks they despise. But there's a fine line between giving basketball players too much autonomy and not enough, and every good coach will tell you that maintaining your principals during those dire moments is the most difficult part of any sport.

"He still thinks as a player, so he says what he would want to hear," Mermuys says. "There's no fear-mongering on his part." During the streak, Luke "tried to pull different levers," his brother Nate says. But nothing led to victories.

When the Lakers returned to Sacramento in December, hoping to end the skid at six, Luke didn't last eight minutes before he stormed the floor and unleashed a profanity-laced tirade at the referees for perceived bad calls against his players. The Lakers lost anyway.

Two nights later in Brooklyn, the Lakers were sluggish in a winnable game and down nine at the half. "In the locker room, we thought he was going to rip into the team," Mermuys says. "Luke, though, was calm. We know where we are, and we know where we want to go. Let's make sure we're seeing the larger picture. Then, as if speaking to himself, he added: It's going to be a long road."

Luke's team stormed back and took the lead, but then it imploded again and lost by 10.

Back in the locker room, Luke searched for the right words, but there was little to say. Perhaps in that moment, seeking another new approach, he thought back to his unconventional upbringing, his charmed and charming life and the brown paper lunch bags scribbled with the lessons of legends.

There is no stronger steel than well-founded belief in yourself.