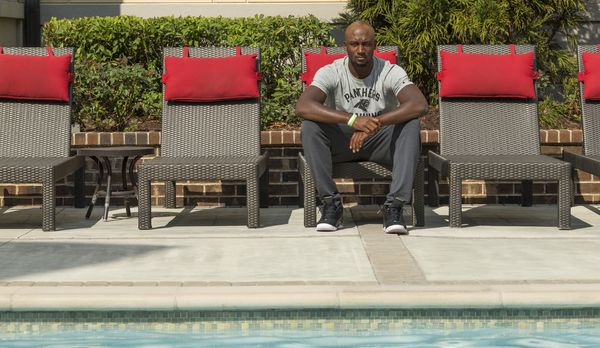

Jason E. Miczek / Special to Bleacher Report

DENVER — He supplies the assessment before being asked for an assessment.

His eyes are cold, his voice curt.

"I f--ked up. Simple as that. I f--ked up."

James Bradberry leaves it at that and continues to pack. He checks the cellphone in his locker and sets it back down. He tucks equipment into a duffel bag. Cracks his knuckles. Nobody along this row of defensive backs in the visitor's locker room speaks to each other for a good 10 minutes after a gut-punch 21-20 loss to the Broncos. Rather, they grab slices of oranges from a bucket nearby, shower and change in slow motion.

For veterans, memories of a Super Bowl loss—buried for seven months—return like a throbbing hangover.

For the rookie Bradberry, this was a grand premiere. A chance to introduce himself to the world. There were 76,843 in the crowd at Sports Authority Field at Mile High and another 25.4 million watching at home. The kid who played in front of 6,259 in his season opener last fall at Samford was now center stage...replacing the highest-paid cornerback in football...wearing the same No. 24...covering 6'3", 229-pound Demaryius Thomas.

So, was it as bad as he thinks? What did this all look like on TV?

In truth, it was not apocalyptic. Thomas had only four catches for 48 yards. But Bradberry's worst fear is letting his teammates down, so the worst plays replay in his mind.

Like C.J. Anderson's 25-yard touchdown on a screen pass. Bradberry grabs my elbows, shoves them together and pretends to push—that's how Thomas took him on a 5.5-second joyride in the fourth quarter.

No, Bradberry wasn't nervous. Really. He promises.

But it was loud. So loud he needed to shout to defensive backs sitting right next to him on the bench.

And his skull was pounding. Bradberry never played at an altitude close to this. At 5,280 feet above sea level, the padding inside his helmet inflated.

"My helmet," he says, "was squeezing my head."

And he rolled his ankle. When Anderson juked Bradberry silly in the first half for 28 yards, the rook knotted up. Upon hearing that word, "ankle," veteran Kurt Coleman shoots Bradberry a death stare from three lockers down. "No, no," he mouths, as if the innocuous detail is akin to disclosing nuclear codes.

Jack Dempsey / AP Photo

"I'm just tired, for real," says Bradberry, falling in line. "It was just a long game."

The first act is over.

On Thursday night, Bradberry was thrust into a starting role on a Super Bowl contender. Not any starting role, either. Bradberry replaced Josh Norman, whose paycheck is now as large as his personality. Whereas Norman actively created his own brand, the second-rounder Bradberry would much rather camouflage in with 52 other players.

One problem: Cornerbacks cannot camouflage in. It's impossible.

You sink or you swim. You're paid or you're cut.

So what's life like for a quiet rookie thrown into this shark tank? Into this vacuum left behind by Norman? Bleacher Report followed Bradberry from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Denver to Charlotte to find out.

Down the hall, take a left into the home locker room and then a quick right and there's Bradberry's first NFL nemesis. Thomas pulls a Led Zeppelin T-shirt over his head, straps on a gold watch and laughs. OK, he admits, he's guilty as charged. Sure, he held Bradberry on that touchdown. A trick of the trade, he explains. Officials are so preoccupied with the back, they ignore the receivers upfield.

In Bradberry, however, he sensed something different.

"If he just sticks to what he knows—and keeps working—his potential is there," Thomas says. "It's just how hard will he work? I haven't been around many rookies who play like he does.

"He's going to be a great player."

The comment is relayed to Bradberry later, outside the team bus. He hardly reacts.

One down. Fifteen to go.

Sunday, Sept. 4, 4:15 p.m. ET

Bank of America Stadium

He emerges from the bathroom with a stack of towels so high it blocks his vision. One by one, Bradberry places a towel on each stool. He's the No. 1 key to the Panthers becoming the first Super Bowl loser to return to the big game since the Bills in 1994, but he's still a rookie.

Still an unknown.

As Bradberry explains, he's always been the unknown. Unwanted. The kid from Pleasant Grove, Alabama, who competed at the Boys and Girls Club from sunup to sundown—crushing peers in "war ball"—leans on a bin in the locker room and counts the ways.

Once, a Clemson coach visited Pleasant Grove High and the two watched film together. In Bradberry's mind, the date was flawless. The coach handed him a business card, left and never contacted him again.

Vanderbilt would've been perfect. Bradberry carried a 3.8 GPA in high school, so the school's academic opportunities were appealing, too. He sent in a recruiting card, and it was sent back with a simple message: He wasn't fast enough for the SEC. Best of luck.

He liked Middle Tennessee State until even it ignored him. The school treated Bradberry like the fallback option before prom, calling him less than 48 hours before signing day. He was livid. He ignored the call.

So off to Arkansas State he went to play the position he always loved: cornerback. But even then, coaches quickly decided Bradberry should move to safety.

This whole week, Bradberry is yes-sir, no-sir stoic with dark eyebrows that never slant in anger. But then he thinks back to the 6 p.m. meeting he called with the Arkansas State defensive coordinator and safeties coach. He told them his plans to transfer, and Bradberry says the coaches tried to convince him to stay. In doing so, they told him he'd never amount to anything at cornerback.

"Off-the-wall stuff," he says. "I was actually starting to think, 'Maybe I'm making a bad decision. Maybe I should stay.' Then when they started talking like that, I'm like, 'Nah, I'm going to leave.'"

Bradberry transferred to Samford, started four seasons, and the Panthers drafted him 62nd overall. Never expecting to go that high, he was fixing his mother's toilet when he was picked. But he was big (6'1", 210 pounds), long (33 ⅜" arms) and, Carolina believes, tailor-made for its defense.

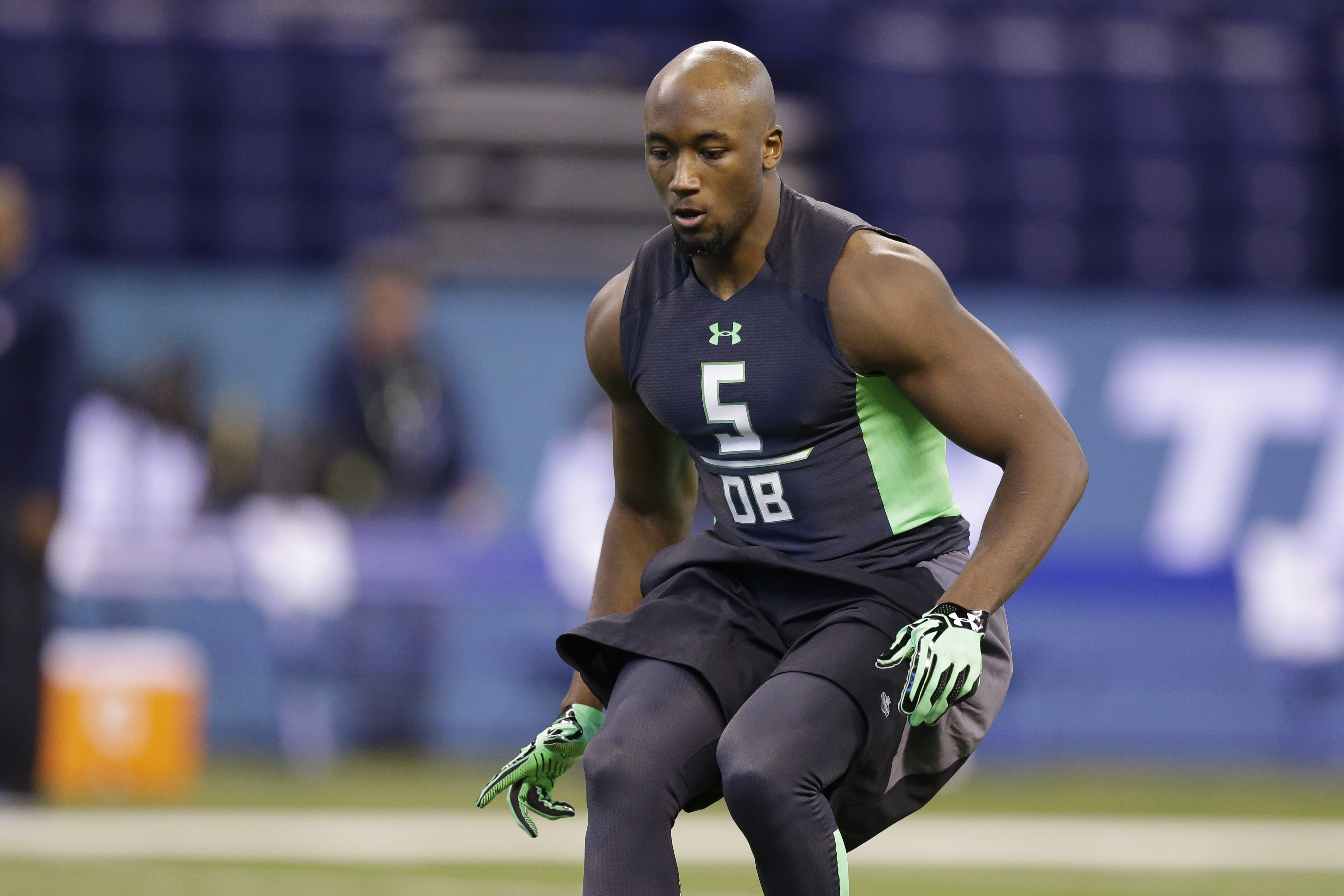

Michael Conroy / AP Photo

Norman was out. Bradberry was in.

"A lot of people may say that because I come from a small school, I can't compete with the bigger-school guys and can't compete at the NFL level," Bradberry says. "I feel like I can do anything the next person can do."

One wave of reporters interrupts. Then, another.

Once everyone leaves, Bradberry looks like he just bit into a lemon.

"It gets frustrating," he says, "because the one thing they always ask about is Josh Norman. That's why I'm ready for Thursday night's game. Hopefully I can put it all to rest."

Monday, Sept. 5, 2:30 p.m. ET

Bank of America Stadium

Each towel is placed on each stool again. Bradberry saunters over to the same bin.

Today's topic? Fears.

He's terrified of heights. If Bradberry is on a roller coaster, he shuts his eyes the entire ride. If he's on an elevator with a window, he looks straight at the doors.

"You know how you're on an elevator and you shift from being inside to going outside?" he says. "I hate that. It makes me edgy."