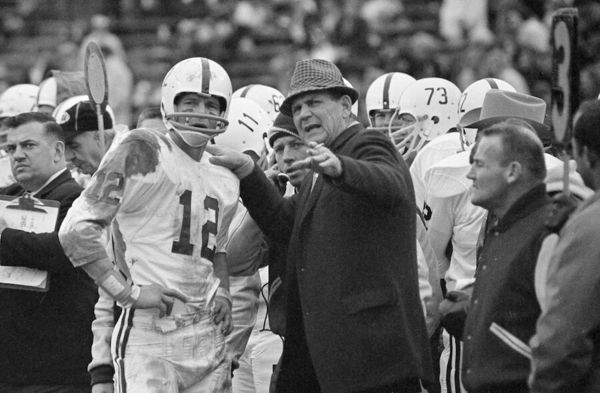

Bear Bryant gives instructions to Ken Stabler in the Cotton Bowl on Jan. 1, 1968. (AP)

EDITOR'S NOTE: In Mike Freeman's upcoming book Snake: The Legendary Life of Ken Stabler, the future Oakland Raiders star has just led Alabama to an 11-0 season and a 34-7 win over Nebraska in the Sugar Bowl. Stabler had been named the MVP of the game and, as Freeman writes, everything was going great for him. "Then came that Corvette. That goddamn Corvette."

There was a reason why Bear Bryant came to tolerate some of Snake’s antics. It’s as old as organized football itself: Snake was too good for Bryant to totally dismiss.

Oh, Bryant would try, prompted by Snake’s behavior. But in the end, he couldn’t. The level of athleticism Snake possessed cannot be overstated. He physically didn’t look the part but in the pantheon of college athletes—from Bo Jackson to Herschel Walker to Tim Tebow—Snake was as good as any of them. He was faster than people thought and stronger than people knew, and the core of his athleticism was a mind that could think quickly under duress.

The three highest-profile quarterbacks in Crimson Tide history are Snake, Bart Starr, and Joe Namath. Each quarterback, interestingly, had issues while at Alabama. In the case of Starr, the coaching staff at the time, and later even Starr himself, engaged in a cover-up over a series of brutal beatings Starr suffered being hazed while trying to get into Alabama’s A-Club for varsity lettermen (Bryant wasn’t the coach yet). Starr was beaten so badly it hampered his college career, led to his rejection for military service, and had an effect well into his NFL life. Starr kept his secret for more than sixty years and only recently did he disclose it.

A clean-cut Snake accepts the Sugar Bowl MVP trophy in January 1967. (AP)

Namath was suspended by Bryant because of one drink of beer. The team had a bye week prior to its last regular-season contest. During that week, Namath went to a local diner, and had just several sips of beer. Not an entire beer. Just a few sips. This still violated Bryant’s policy that players were not allowed to consume any alcohol during the season. Since Bryant had sources in every diner, outhouse, farmhouse, and henhouse in Alabama, it was only a matter of time before he heard about Namath’s beer-sipping exploits.

What happened next is the kind of thing that led so many players to cherish Bryant. After the suspension was announced, and as every newspaper across the state began looking for Namath, the coach who had suspended him hid him in his house. Namath ate home-cooked meals and enjoyed the hospitality of the man who suspended him. On the surface, such an arrangement seems, well, awkward. Not at Alabama. To Namath and Bryant, the punishment was transactional, not personal, and Namath was mature enough to understand that.

Okay, but back to the Corvette...

Snake decided that after beating Nebraska in the Sugar Bowl, he was going to treat himself. Most players under Bryant went out to get a burger to treat themselves. Snake was different. A burger wouldn’t do. A car would.

And not just any car. Snake wanted a new 1967 Corvette. The gall needed to think that he deserved a Corvette when he didn’t have credit...or money. Not even a damn dime. But this was Snake. The fact he wanted a Corvette wasn’t arrogance. It was exuberance together with an understanding of the system. He understood the college game, and how much money (even then) it generated for the school. To Snake, he figured he’d get a piece of the action. He caught a ride to Birmingham and went to a car dealer, one that he knew had strong ties to Alabama. When Snake walked in and introduced himself, the salesman’s eyes lit up. "Snake Stabler!" he exclaimed. "I saw you win Most Valuable Player in the Sugar Bowl. You guys just stomped the s--t out of them Cornhuskers."

So, yes, the salesman was an Alabama fan. This was going to be easy, Snake thought. "You know the contract Joe Namath got when he went pro?" Stabler wrote in his autobiography. "I’m going to be a top pick, too. When I sign, I’ll have a bunch of money. You just carry me till then and I’ll pay off the whole note when I get my bonus." Snake wasn’t lying. He did indeed pay off the car note once he was drafted by Oakland. The car cost about $5,700, or $40,000 in today’s dollars.

Then while driving to Mobile to show off the car to a woman he liked, and hoping to utilize it like an aphrodisiac, he drove into a car stopped at a red light. There was extensive damage to the front of the car. Nothing was going to stop his date in Mobile, so he borrowed another car and made the trip. He arrived and told the woman it had been quite a morning already. "I started out today in a new Corvette that I bought without a cent down and no known credit," he told her. "You don’t happen to know anyone who’s good with fiberglass, do you?"

"No," she said, "but I’m good with some other things."

It was good to be Snake.

✦✦✦

The telegram from Bryant to Snake was almost bone chilling in its succinctness:

YOU HAVE BEEN INDEFINITELY SUSPENDED

COACH PAUL W. BRYANT

Again, it all started with that Corvette.

The woman’s name? It’s unclear. What is clear is that Snake was infatuated with her. Initially he took the Corvette to see her in Mobile just once a week, but then it became three or four nights a week. Initially, Snake followed the rules at Alabama. Hell, he earned the award for the neatest dorm room, but there was always a part of Snake that was a self-saboteur. Off the field, there would be no conforming.

Snake’s trips to Mobile to see the young lady became expensive in both dollars and capital with Bryant. He started skipping more and more classes. The reason was the commute. As fast as the Corvette could travel, it still wasn’t a rocket ship. His first class was at eight in the morning, and he’d leave for Mobile at nine the night before. Snake would spend two hours with her and then head back. He’d miss that first class. In the beginning, just a few. Then more. Then all of them. The same with some of his other classes. Soon he was flunking them all.

"It was not easy for football players at Alabama to fail courses, particularly education majors," wrote Stabler in his biography. "All you had to do was show up."

Stabler takes a hit in the 1967 Sugar Bowl. (AP)

(Namath had one of the best jokes about Alabama and academics when he spoke to reporters on a plane ride to New York for his first press conference. "What was your major at Alabama, Joe, basket weaving?" Namath didn’t miss a beat. "No, basket weaving was too tough. So they put me in journalism instead.")

There were, also, six speeding tickets in two months during Snake’s trips between the dorm and Mobile. Eventually he did something almost fatal: he stopped going to football practice.

This was Bear Bryant. You thumbed your nose at his rules at your own peril. As much as Snake deified Bryant and respected him, Snake didn’t fear him. After all, Snake had had a violent, alcoholic father. After that, there’s little that scares a young man.

"My dad saved me," Snake would say, years later.

One of Slim’s friends was an attorney who composed a fake letter that read like a letter from the army. The letter stated that if Snake didn’t return to football, he’d be drafted and sent to war. It was an immaculate lie, and it worked. Snake panicked and began to try to work his way back into Bryant’s graces.

The first thing Snake did was reregister for classes to gain back his eligibility. Bryant wasn’t impressed. They saw each other one day on campus, and when Snake told Bryant he’d make up for his transgressions, Bryant didn’t believe him. "Maybe you should play baseball," he said, and the conversation was over. Stabler had a long way to go before Bryant would forgive him.

Snake was trying hard to return. It was genuine. The women were still there—there was a new one, in addition to the woman in Mobile—but nothing was going to stop Snake from working his way back on to the team. The switch that caused Snake not to give a s--t, the rebellious Snake, was flipped back to the off position. Snake regained his eligibility and in the summer, two weeks before the start of camp, he went into Bryant’s office. He’d rarely been so nervous.

Stabler with the Oakland Raiders in the late '70s. (Rogers Photo Archive/Getty Images)

Bryant was sitting and smoking a cigarette. Snake remained standing. "I’m ready to return, Coach," he said. "I worked hard all summer."

Snake recalled Bryant just glaring at him, silently, smoking and spitting tobacco into a cup. "Stabler," Bryant told him, "you don’t deserve to be on this team."

Bryant was angry with Snake, but he knew Snake was one of the most talented players he’d ever seen. Bryant just needed to reestablish who was the boss and he needed it to be extra clear for Snake—that no matter how much he despised the rules, on a Bryant team there was no exception to them. It didn’t matter how special a player was. Once Bryant saw that Snake understood this, he sent word to allow Snake back on the team.

Snake celebrated by buying a six-pack, hopping into the Corvette, and driving to Foley. He took the empty beer cans and tossed them out of the sunroof, aiming for stop signs. He hit most of them.