He crouched at the back of the 70-foot yacht, tightening his grip on the urn as he extended it over the Pacific Ocean.

Adorned with spiked metal studs and hot-pink rhinestones spelling out CHYNA, the vase would’ve seemed gaudy in most circles. But for a mink coat-wearing WWE icon muscular and imposing enough to be dubbed “The Ninth Wonder of the World,” it couldn’t have been more fitting.

“You getting this?” the wrestler’s manager, Anthony Anzaldo, said as he scattered his client’s ashes into the saltwater. A videographer nodded and moved in tighter.

“OK, have you done the slow-motion shot yet?” Anzaldo said, pausing before he dumped more of the remains.

In some ways, this is how Joanie Laurer would’ve imagined her final send-off: the bedazzled urn, the $1,500-an-hour boat, the extravagant burial at sea just three miles from her home in Redondo Beach—all of it captured on film for a documentary about her life.

From the time she made her WWE debut as Chyna in 1997 to the moment this April when she posted a YouTube video of herself chugging a spinach smoothie just hours before a lethal drug overdose at age 46, Laurer always welcomed the spotlight.

At times, some say, she craved it.

Still, according to dozens of people who knew her the best, including many who tried to save her, the scene on the yacht also magnified the part of Laurer’s life that was missing—the part that had long been hollow.

Kicked out of her home at age 16, Laurer hadn’t seen her mother in 30 years. She cut off communication with her sister more than a decade ago, infuriated at the suggestion that she enter a drug rehabilitation facility.

Laurer cherished the identity and acceptance she found in WWE, where former colleagues say she became one of the most popular wrestlers on the roster. But she alienated many of them after leaving the company in 2001, when her life began a 14-year spiral peppered with arrests, porn films, reality shows, suicide attempts and videos on TMZ.

The health nut whose gym bag was stuffed with protein powders and vitamins began swigging Jack Daniel’s, smoking Marlboros and popping Valium. A concerned friend went to check on Laurer and discovered the former Playboy model—who once earned more than $1 million in a single year—living with a homeless man in a tiny apartment void of furniture, save for a naked air mattress on the living room floor.

In 2013, the former role model who one colleague said “did more for the empowerment of women than Billie Jean King” was discovered bloodied from self-inflicted knife wounds in the streets of Tokyo. Laurer, a friend recalled, swung her weapon at responding police officers, who tackled her, put her in handcuffs and drove her to a mental hospital. She would spend the next month “locked up in a confined room.”

“It’s one of the most disheartening illustrations I’ve ever seen of what mental illness and drug abuse can do to a person,” WWE Hall of Fame broadcaster Jim Ross said. “The saddest part is that, at her core, Joanie Laurer was a very loving, sweet person—a gentle soul.

“She just couldn’t overcome her demons.”

Two months after her death, no family members traveled to Redondo Beach for Laurer’s public memorial service on June 22 or her burial the next morning.

Instead, as the ashes of the most famous female pro wrestler in history danced away into the Pacific, her mourners included the manager and his four children, an ex-boyfriend she hadn’t seen in 11 years, a rented preacher reciting a prayer off a wrinkled notecard and two members of Laurer’s social media team she had never met.

✧✧✧

As she snorted the crystal meth, Joanie Laurer could hear the pounding on the door, but she wouldn’t let her sister inside.

Earlier that afternoon in March 2003, Kathy Hamilton had arrived unannounced at Laurer’s condo in Marina del Rey, California, and pleaded with her sister to seek help for her addiction. Laurer screamed and cursed at Hamilton for hours before barricading herself in the bathroom to get high.

“I didn't recognize the person I saw that day,” says Hamilton, who had come from her home in New Hampshire. “It was like the devil had invaded Joanie’s body.”

Later that evening, with the help of an interventionist, Hamilton convinced Laurer to check into the Chateau Recovery Center in Utah. A private plane flew the sisters to Salt Lake City, and they arrived at the facility around midnight. Five minutes later, as staff members attempted to greet her in the lobby, Laurer went on a profanity-laced tirade and stormed out.

“I don’t know why the f--k I’m here,” she screamed. “I’m not doing this.”

Laurer flew home the next morning and never spoke to Kathy again. For years, though, she sent threatening messages via voicemail, postcard and fax.

“I can’t believe you deserted me.”

“You’re going to pay for this.”

“I’m going to come get you.”

“I lived in fear of my sister for a long time,” Kathy says. “I was literally scared she was going to show up at my front door with a knife or a gun.”

“I didn't recognize the person I saw that day. It was like the devil had invaded Joanie’s body.”

In Hamilton, Laurer lost not only her sister, but also her best friend, the only one who had supported her during tough times. Goodness knows, there were plenty of them.

Growing up in Rochester, New York, the Laurer children weren’t close with their biological parents, Janet and Joe. The couple lived on welfare, bouncing from one low-rent apartment to another. Twice a year Janet’s mother and father drove their grandkids to Sears to buy them clothes—three outfits each for Kathy, Sonny and little Joanie to wear to school, where they qualified for the free lunch program. Compassionate neighbors occasionally paid for the family’s groceries.

An alcohol and gambling addict, Joe Laurer cheated on his wife, often disappearing for days at a time. When he got home, he beat Janet in front of their children.

Kathy remembers one drunken episode when her father chased Janet through the apartment with a butcher knife, stabbing her in the leg. As the police led him away, she recalled, Joe yanked off his wedding ring and threw it into the yard.

Janet was on her third husband by the time she kicked Joanie out of the house at 16, furious after catching her daughter with marijuana. The two never saw each other again.

“She was done being a parent and done being stressed out,” Kathy says of her mother, with whom she hasn’t spoken in 20 years. “She just gave up.”

Laurer moved in with her father and finished high school without many friends. After graduating from the University of Tampa in 1991, she spent time in the Peace Corps in Costa Rica. She worked as a cocktail waitress at a Tampa gentleman’s club and delivered singing telegrams. She helped sell cars and trained to be a flight attendant. Nothing seemed to stick.

The one constant, however—the one thing that gave her solace—was weightlifting.

Laurer’s interest in bodybuilding started during her teenage years, when she often went to the health club after school and stayed until it closed. But it became an obsession after she left Florida and moved in with Kathy in Londonderry, New Hampshire. Whenever she wasn’t selling beepers or teaching aerobics, Laurer was at The Workout Club with her sister. It was there Laurer met and started dating her personal trainer, Gerry Blais.

Six days a week, Blais would wake up Joanie at 4:30 a.m. and drive her to the gym. Early-morning lifts were followed by boxing sessions in the afternoon. At night, Joanie would cram 80 pounds of weights into her backpack, drape it over her shoulders and then spend 30 minutes on the StairMaster.

It wasn’t uncommon, Blais says, for the 5’10” Laurer to squat 450 pounds a dozen times. She could bench multiple reps of 315 pounds. Her meals almost always consisted of fish or chicken, protein powder and vitamins. Once a week, on Sundays, Blais allowed Laurer to slip into a “carb coma”: blueberry pancakes, pizza, apple pie with ice cream—anything she wanted.

Laurer had gone from 155 to 185 pounds—“all natural, all pure muscle,” Blais says—in a matter of months.

Everywhere Joanie and Kathy went, people stared. Competitors on the fitness contest circuit suggested they become a pro wrestling tag team—“a sister act,” they said, and Kathy laughed.

Joanie, though, was intrigued.

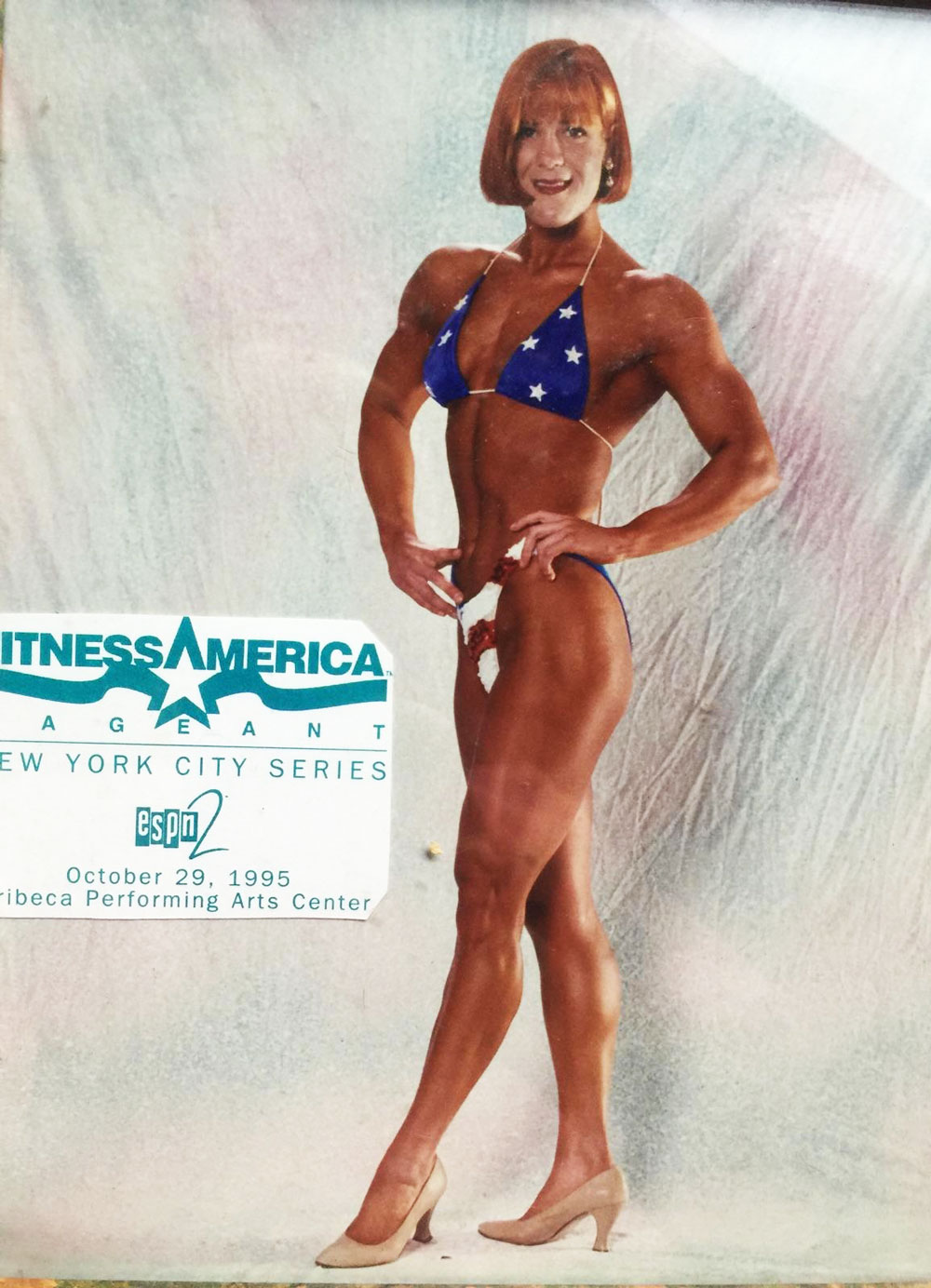

Laurer during competition in 1995

Wearing blond wigs and sleeveless tops to show off their physiques, Joanie and Kathy attended a WWE event in Malden, Massachusetts. Their presence created a sideshow, with fans turning away from the ring to gawk at the chiseled women in the crowd. Kathy wasn’t comfortable with the attention, but Joanie loved it. For the first time in her life, she felt powerful.

“They’re looking at us like we’re someone,” Joanie said.

The following day, she and Blais made the 95-mile drive back to Malden to meet Wladek “Killer” Kowalski, then a 68-year-old WWE Hall of Famer who ran a wrestling school in the area.

“From the minute we walked through that door, he couldn’t stop staring at Joanie,” Blais says. “He had this look in his eyes like, She’s different. She’s special. It was the weirdest chemistry I’ve ever seen. He knew. He just knew.”

Laurer and Wladek “Killer” Kowalski

Laurer began training with Kowalski and wrestling for his independent promotion, where her first match was against a man dressed as a woman, complete with makeup, a blonde wig and a goofy ring name: Snooki.

As word of her build and athleticism began to spread, Laurer drove to a WWE show in Massachusetts in January of 1997, watched the matches from the stands and then waited for an hour outside the locker room after the event ended. When stars Shawn Michaels and Paul Levesque—aka Triple H—emerged, Laurer introduced herself and expressed interest in joining the company. After a brief discussion a storyline was born: Laurer could pose as a female bodyguard for some of the company’s biggest stars.

Triple H loved the idea and was confident his bosses would too. With other promotions also reaching out, an opportunity seemed imminent.

“She came home that night and never slept,” Blais says. “We knew her life was about to change. She was so excited.

“And also a little scared.”

✧✧✧

The phone call came shortly after 6 a.m. from New York’s Times Square.

“Kathy, wake up,” Joanie told her sister in January 2001. “I’m in the back of a limousine, on my way to be on Good Morning America.”

Now in her fourth year with the WWE, Laurer’s voice was filled with energy. “Chyna”—the nickname given to her by company President Vince McMahon—was experiencing a level of popularity she never could’ve fathomed.

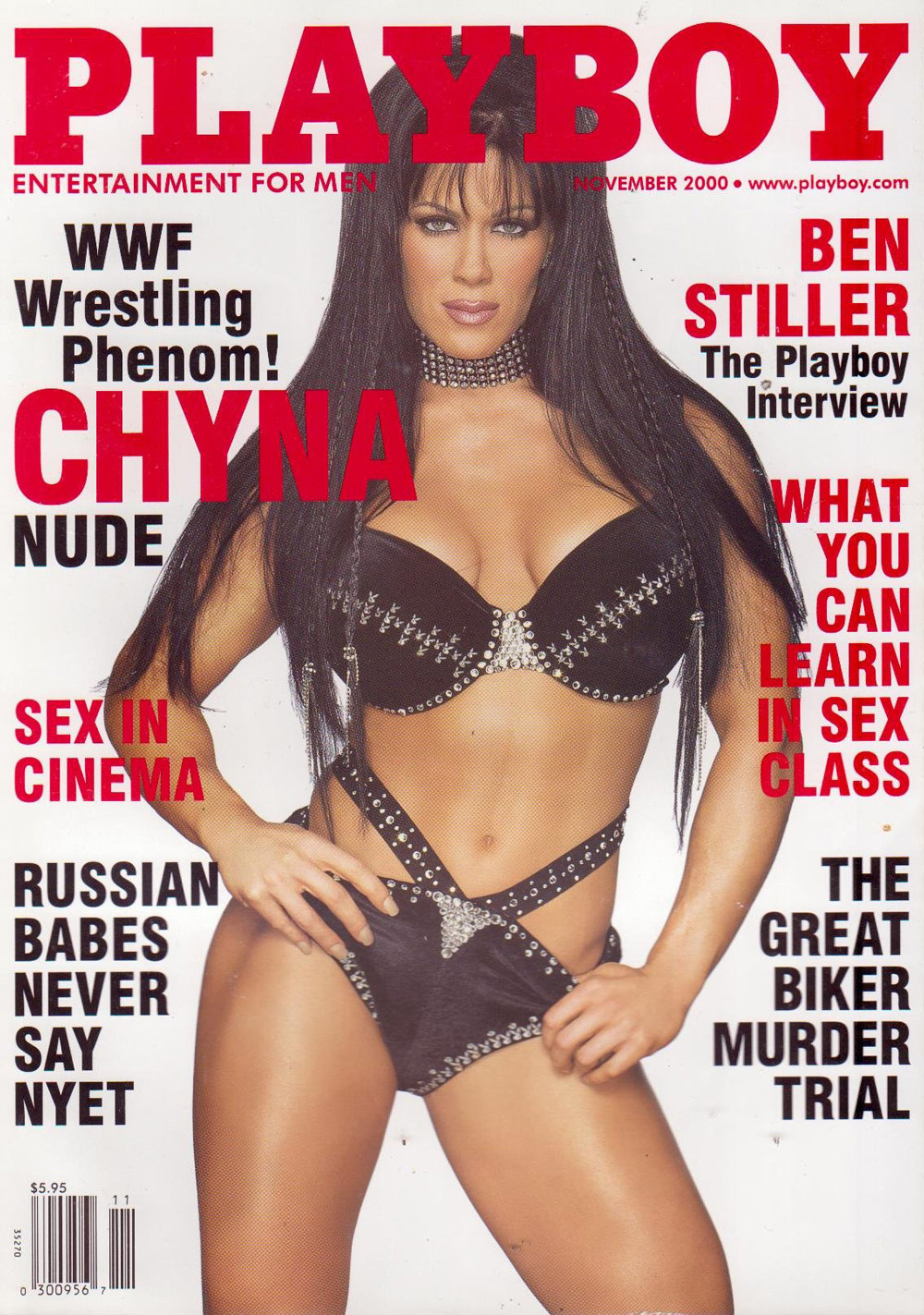

Two months earlier, an issue of Playboy magazine with Laurer on the cover reportedly sold more than a million copies. Her autobiography, If They Only Knew, had reached the New York Times bestseller list, and she’d appeared on The Tonight Show as well as the covers of Newsweek and TV Guide.

Laurer's November 2000 Playboy cover

“She felt like she’d really made it,” Kathy says. “She loved being treated like a rock star.”

And living like one.

Almost immediately after she signed with WWE in 1997, Laurer’s wardrobe transitioned from pullovers and sweat pants to minks and designer jeans. She’d purchased a baby grand piano and replaced her Ford Probe and its bent antenna with a cherry-red Audi.

Some of Kathy’s favorite memories are of giggling with Joanie late into the night as they used her sister’s credit card to purchase thousands of dollars’ worth of lingerie from a Victoria’s Secret catalog, the two taking turns ordering an item apiece.

Ross, the broadcaster who also served as the WWE’s head of talent, estimated that Laurer’s total earnings in 2000 surpassed $1 million.

“The business had never seen anything like her,” Ross says.

Before Chyna, women in pro wrestling were dismissed by a male-dominated industry as sex objects, all skimpy outfits and novelty appeal for video games and posters in teenagers’ bedrooms.

Laurer was completely different. Now bench-pressing 365 pounds, her blend of size and strength was so extreme that she felt awkward in the ring with other women and feared she would injure them.

WWE execs went to McMahon with a suggestion. Andre the Giant had already been dubbed “The Eighth Wonder of the World.” The Ninth Wonder would wrestle men.