Iconic actor Jack Nicholson lives not far from here.

This comes up because Lenny is telling me about stopping by Jack's house just the other day to get a blurb for the book jacket.

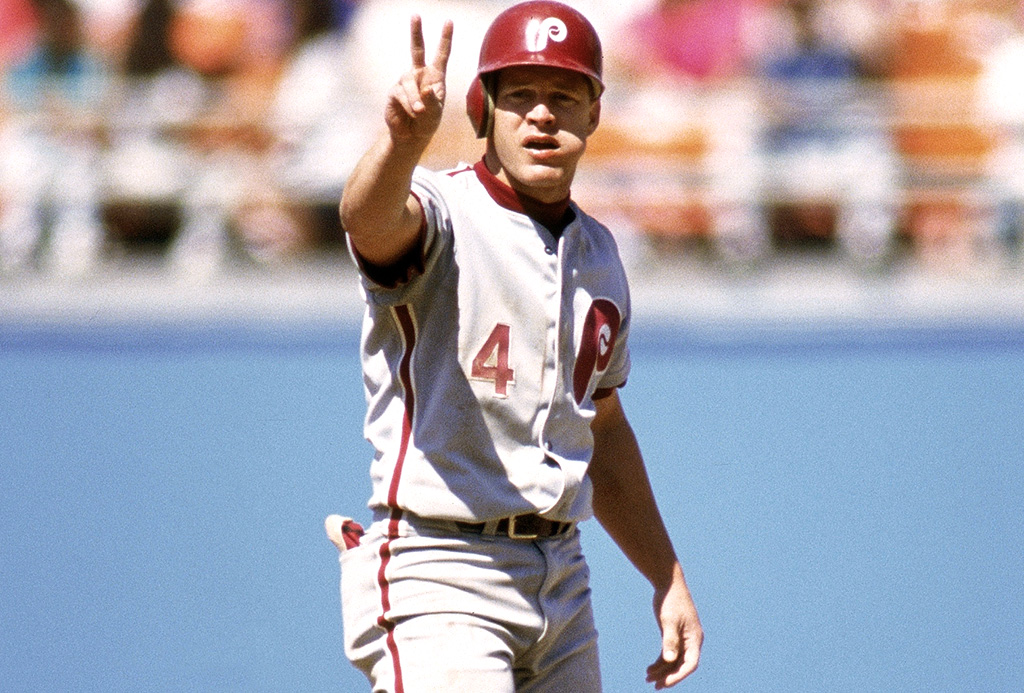

According to Dykstra, the two have been longtime friends, dating back to when the outfielder would leave tickets to games at Dodger Stadium for the star of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and other classic films.

Affecting a dead-on Nicholson imitation, Dykstra says he would often hear the actor cackle "Where's ol' Nails?" as Dykstra approached the stands before games.

Ah, the days of fast times and All-Star appearances (1990, 1994, 1995).

"C'mon, how can you not take drugs? I'll go make $60,000 and take orders from somebody while you go make $30 million? Money changes things."

- Lenny Dykstra

But after baseball came a string of other ventures. First came the car washes in Southern California, then a string of other businesses that led to his spectacular crash and much of his family cutting contact with him. At one time, he was writing a financial advice column with Jim Cramer's TheStreet.com. At another, he attempted to launch a high-end charter jet company. And the magazine? It ceased publication after he filed for bankruptcy in 2009, leaving some employees unreimbursed for expenses

Promises, broken.

"Remember, though, I didn't get stupid overnight," Dykstra says, the pretenders continuing to walk by the patio on this Southern California night. "I was pretty f--king smart. I built this magazine called The Players Club. I didn't build a magazine because I wanted to get in the magazine business. It was a conduit, or a tool, to get to players. But I only did that because I had my partner, AIG, the biggest insurance company in the world, bankrolling me.

"Then they went f--king bankrupt. What the f--k? (For the record, AIG was folded into a $182 billion government bailout program.) And the bank that gave me my loan on the Gretzky house, they went bankrupt. In 2008, the whole world dried up. Yeah, man.

"But I don't want to come off as somebody that's making excuses. I didn't have to buy the Gretzky house. But when the biggest bank in history goes down, when they tell you we're going to put you in this loan and your payment is going to be this much, and they say, 'OK, you're not going to bankrupt your own customer, are you?' They were into predatory lending. All of them were. "

Washington Mutual, the country's largest savings and loan association that collapsed in 2008, was his lender, Dykstra says.

"But the story's not about pity," Dykstra continues. "I mean, there's nothing else to really talk about. Have I done things that I'm not proud of? Yeah, I admit that, I have. But did I ever do anything that justified me getting locked in a cage for two years? No. I didn't.

"And there's real deep reasons why that happened, too hard to even explain. And people wouldn't get it and they'd think, 'There he goes again, blaming everybody else,' so I don't even want to go down that road.

"The thing about it is, I look at what happened, and you've gotta learn from it, you know? I've never been a pity guy. That's not how I roll."

"Have I done things that I'm not proud of? Yeah, I admit that, I have. But did I ever do anything that justified me getting locked in a cage for two years? No. I didn't."

- Lenny Dykstra

One aspect of the family business, the baseball part, continues rolling today: Luke, 20, is hitting .319/.352/.375 for the Rome Braves, the Class-A affiliate of Atlanta.

And while the Nationals' Harrisburg affiliate released Cutter, 27, in early June, he has turned his father into Grandpa Nails: He and Jamie-Lynn are the parents of Beau, now 2.

Luke, meanwhile, was Atlanta's seventh-round pick in 2014 and currently appears to be the better prospect.

"Great kid," Braves general manager John Coppolella says. "He's a baseball rat. A gamer.

"No off-the-field problems."

Speaking of which, Dykstra's life today is completely different than the one he once imagined.

"I've always had a great relationship with my kids, you know?" he says. "By the grace of God, or whatever power is up there, I was able to get out in time for my Luke's senior year of high school."

His ex-wife, Terri, he says, asked him to move back into the house during that time to help with Luke.

"So, like, Terri, she got a job working for an oral surgeon," Dykstra says. "I remember one day I'm doing the dishes and Terri comes home from work.

"I look at her and she looks at me and I said, 'What a world. I'm f--king doing the dishes and you're coming home from work. What a 360."

Lenny Dykstra of the New York Mets looks on during batting practice prior to the start of a game circa 1986 at Shea Stadium. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

So, Lenny says, he got to spend the entire eight months of Luke's senior year helping to prepare him for pro ball.

"See, the public doesn't really have an idea," Dykstra says. "There's baseball and there's pro ball. Meaning, you're together almost seven months. So you have to have something you can depend on and you can trust to take up to that plate, or you're going to go f--king haywire. It wasn't until I learned that on my own, meaning the right way to hit and the right way to play, which would have made it a simpler game. Instead of wondering and trying different things.

"There's only one way to hit. You either hit right or you hit wrong. If you see a hitter up there and count is 1-0 and he's a right-handed hitter and he hits a foul to the first base dugout, he doesn't have a clue what he's doing. You gotta be guessing. You have to guess the extra strikes. Half the players, I guess, [don't even try] taking like a strike in the ninth inning when you're down two runs. Think about [swinging], that's selfish. Even if you hit the motherf--ker, there's a 70 percent chance you're going to make an out.

"It's changed. There are things they can get away with because they have so much talent. But at the end of the day, they're still cheating themselves, their teammates, the fans, the organization, from doing the job they could do if they had the discipline to play right."

Dykstra thinks back to his own playing days.

"When the game would end, I would always go and sit in front of my locker just for two minutes by myself and say to myself, 'OK, if I was a fan, would I have paid money to watch myself play tonight?'" he says. "That's how I judged myself. Even if I took a collar or something, if I played right, good fans know. So many guys play wrong now. It's very disturbing."

He excuses himself to go to the restroom. As he does, he hands me his laptop and invites me to scroll through some pictures that will appear in House of Nails. He is beyond excited to share his story through the book's pages. There he is with Darryl Strawberry and Doc Gooden. In the World Series. As a skinny kid. As a steroids-addled Hulk. It's all there.

"When the game would end, I would always go and sit in front of my locker just for two minutes by myself and say to myself, 'OK, if I was a fan, would I have paid money to watch myself play tonight?' That's how I judged myself."

- Lenny Dykstra

When he returns, he says he has to go, that he's got a friend waiting. He starts glancing toward the sidewalk frequently, as if something else is out there.

Wait, I tell him. I thought I was going to give you a ride back to your house and we were going to talk awhile longer?

No, man, he says. He can give me the real story, but first I need to get the green light from my editor that everything is a go, and then my guy must talk with his guy.

Lenny, I say, I have the green light. Why else do you think I drove up here for dinner?

We'll talk, he says. You driving home tonight? Why don't you call me on your drive home and we can talk some more?

But Lenny, I'm here right now and—

His laptop screen now is showing a picture of his private jet from back in the day. He rhapsodizes about making a snap decision to fly to Italy.

"Beyond cool," he says. "Addictive. P---y's taken countries down. It's literally made people make bad decisions. But when you've got a plane, f--k dude. It makes p---y look like a red-headed stepchild. It's crazy. And I loved it. Had a good plan, too. But there's so many things..."

So many things. Writing this book, he says, is the most difficult thing he's ever done in his life. Except, he started with a noted co-author, Peter Golenbock, but says he fired him because Golenbock couldn't find his voice. B/R sources say Golenbock wrote much of the book but was lopped off of the project before Dykstra had to share any significant money with him.

"I've written books with some of the greats in baseball, and I couldn't get his voice?" Golenbock tells B/R.

Looking back, Dykstra had an All-Star baseball career, things went south on him afterward and, now?

It's why he's calling the company he created for this book the "Third Chapter." Because the first chapter of his life was "great," the second chapter was "ehhh" and the third chapter "hasn't been written yet."

"So you should talk to your guy about what he wants," Lenny says, rising to leave. "If you want a big swinging dick story, I can do that. Pictures, everything. I'm talking about behind-the-scenes stuff."

He asks me to turn off my tape recorder. It is nearly 9:30 p.m. as we exit the steakhouse, with Lenny alternately insisting he has a friend with him or that a friend is waiting. Something. As we stand on the sidewalk and say goodbye, a white sedan pulls up and Lenny hops in.

In a corner of the front window, a placard contains the logo for Lyft.

The red meat lived up to its billing. The creme brulee? Good, if not mind-blowing.

Then again, not everything comes as advertised.

Meanwhile, as the pretenders continue walking by, the sedan pulls clear out of sight.

Scott Miller covers Major League Baseball as a national columnist for Bleacher Report. Follow Scott on Twitter and talk baseball.