In April 1991, Maiorana was playing for the reserves against Aston Villa at Old Trafford when he went in for a challenge with Dwight Yorke and ruptured a ligament in his knee. He would need surgery.

"That day changed everything, and spelt disaster," he says. "I knew I had done something bad. It was when doing your cruciate could finish you, and they said I would have been better breaking my leg."

Even when he had been fit, Maiorana was an outsider. So now, unable to play, his isolation at Old Trafford only increased as he watched the emerging class of 1992 overtake him.

"I got on with Ryan [Giggs], David [Beckham], Paul [Scholes]—they were great people," he says, "and I can remember the reserve team manager Brian Whitehouse telling me, 'Jules, listen. I have got this young kid coming up called Ryan Giggs,' but I believed in myself so much that it didn't bother me.

"However, when I saw that the Beckhams and the Nevilles had squad numbers and I didn't, I knew the writing was on the wall."

In May 1993, Maiorana was recovering from another operation when he received a letter from United thanking him for his service and informing him he was free to approach other clubs.

"I got a meeting with Ferguson in his office, threw the letter down on the table, pulled my jeans down to show him my scars and said, 'If I walked in to your club, would you give me a job when I look like this? No one is going to give me a contract,'" Maiorana says. "He told me to take the £25,000 insurance, but I didn't want to give up. He relented and gave me another year, walked out and patted me on the back and said sarcastically, 'I really like you, Jules.'"

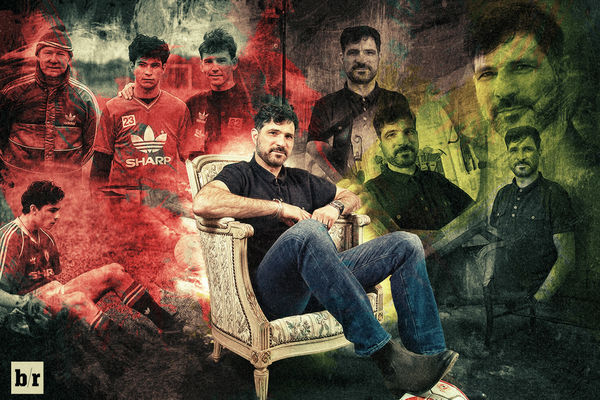

Image posted on Twitter by @whitesideone of Maiorana signing for United in 1988.

Twelve months later, nothing had changed, and after only eight games over six years, Maiorana had to walk away from Old Trafford.

"I can recall saying to myself, 'Football can go f--k itself,'" he says. "I was furious. I washed my hands of the game."

After a brief comeback alongside his former United team-mate David Wilson in Sweden with Ljungskile SK, Maiorana was forced to retire from football. He was only 25.

Back in Cambridge and unable to play, Maiorana worked in the family upholstery business again but struggled with his new reality. He never envisaged being back there so soon.

"I slunk home," he says. "I had come full circle and doing what I had done 10 years before. Oh, I was angry. I was so angry it had come to this. I went to some dark places. I struggled big time. I was thrown on the scrap heap. No one cared about me. I even went to see a shrink, but they actually said I was all right. I got no help from the club whatsoever."

"Six years earlier, he had left Cambridge a happy-go-lucky 19-year-old who was loving life," recalls Maiorana's older brother Salvatore, who today works with him in the family business. "Then he came back, and he had had his world ripped away from him. He had changed, and he was in a mess. He wasn't getting out of bed for work. He just didn't want to be back with us again."

Screenshot taken of a post on Maiorana's official Twitter account.

For the next seven years, Maiorana banished football from his life. He didn't play or attend a game, and he didn't watch a game on television. He refused to even glance at a game in his local park.

"But I couldn't get rid of it entirely from my head," he says. "I would be working and then storm out upset. I would go to bed thinking about football, wake up thinking about it. Those were the demons I fought. It was so hard to forget about football."

On the few occasions he was recognised in the street, he would deny it was him.

"If I could have erased all my United memories, I would have done," he says. "Just got rid of all of them."

But in recent years Maiorana has begun to slowly make peace with his past.

"I went to some dark places. I struggled big time. I was thrown on the scrap heap. No one cared about me."

"My son encouraged me to get on Twitter, and some United fans have got in touch," he says. "A few years ago, someone told me it was 25 years ago to the day that I made my debut, but I had no idea, so I had a beer to celebrate that night. Someone also said, 'You made a bigger impact than Memphis Depay, and we paid £25 million for him.' Overall, things do feel better now. It is nice talking to you."

There are still no pictures of him playing for United on his walls at home, but occasionally Maiorana will look at his United mementoes, which are kept in a pillowcase in his loft.

But this rapprochement has yet to extend to Ferguson.

"No, I haven't made my peace with Ferguson, not at all," he says. "I would like to bump into him now I am a proper man and not just a kid."

Post on Maiorana's official Twitter account.

Maiorana has seen Ferguson just once since he left Old Trafford. It was seven years ago at the funeral of Medwell, the United scout who had discovered him.

"A funeral was obviously the one place where I couldn't say anything," he says. "To be fair to him, he came and spoke to me, and we had a brief chat. He said, 'You're looking good, Jules.' I said, 'I am surprised I didn't lose my hair playing under you.' He said, 'You would have if you'd stayed a year longer.' He is very sharp."

Today Maiorana runs the upholstery business from a workshop next to his home in Cambridge, and even manages to play some five-a-side, though his knee can swell up.

"I try to bring out the old moves, but the legs can't do it," he laughs.

He is content now. The bitterness and sense of regret have faded. He is prepared to embrace his past and feel proud about it.

"Yes, I am proud about getting to United from Histon," he says, "but I will never be proud of what I achieved there; it wasn't that much. I am proud of the rise, but not the career."

What he achieved was something for the ages.

"Before he died, Ray Medwell said to me what I had achieved in football will probably never be done ever again," Maiorana says. "A kid from Histon, who had been playing five-a-side a few months before that, going on to play for Manchester United. That was once-in-a-lifetime stuff."

On the morning I meet Maiorana, he acknowledges he had been in his workshop and—possibly prompted by my visit—had allowed his mind to wander to thoughts of how, if things had worked out differently, he could have enjoyed the same career as Giggs or Beckham.

Still, he says, his time at United means nothing to him.

"I only played a handful of games, but the best thing about my time in Manchester is I met my wife Val there," he says, "and we have had two great kids, and that will always mean more to me than football. And I mean that from the bottom of my heart."

Original photography by Jon Super for Bleacher Report. Lead artwork by Virgo A'Raaf. Images courtesy of Getty. All quotes and information obtained firsthand except as noted.