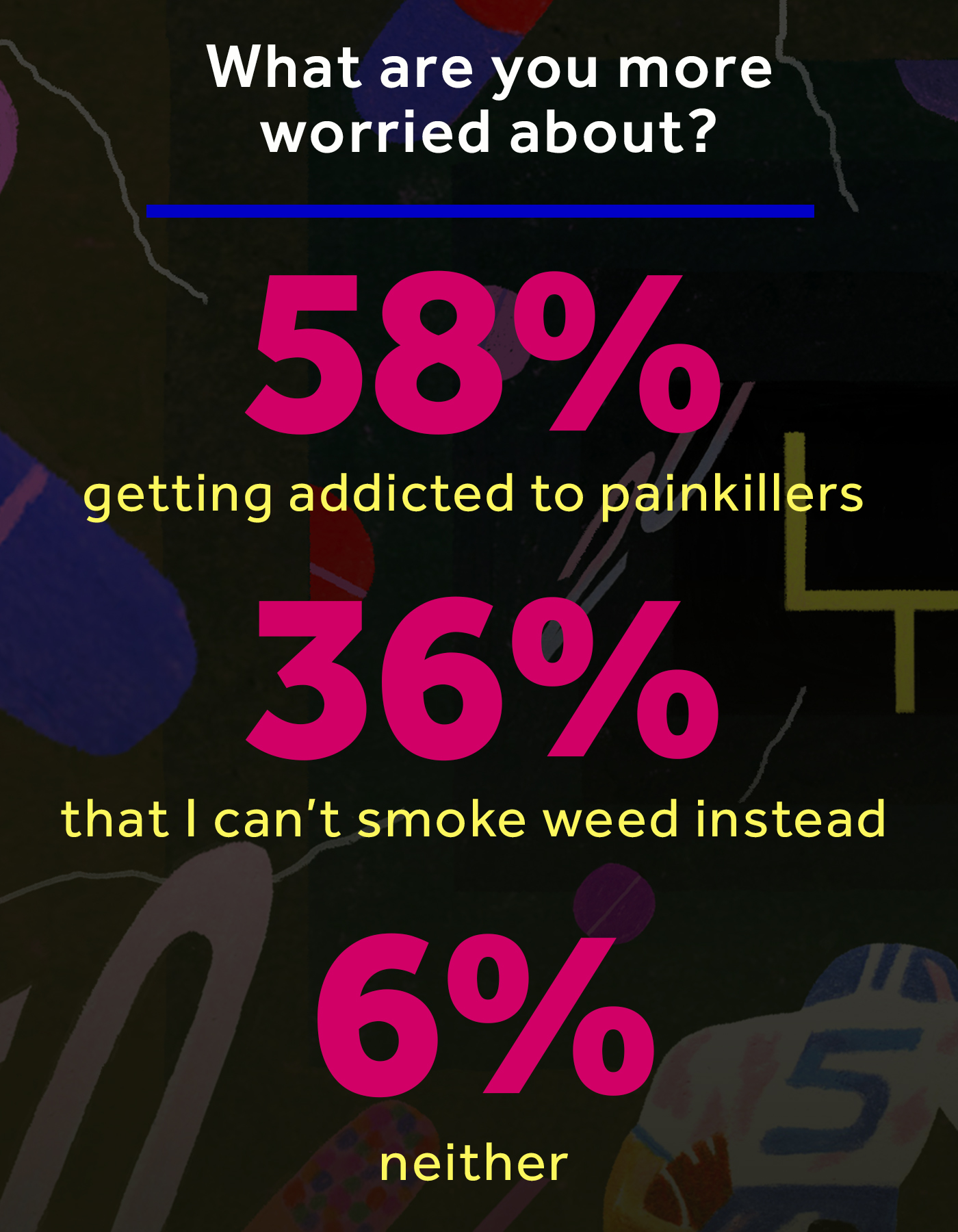

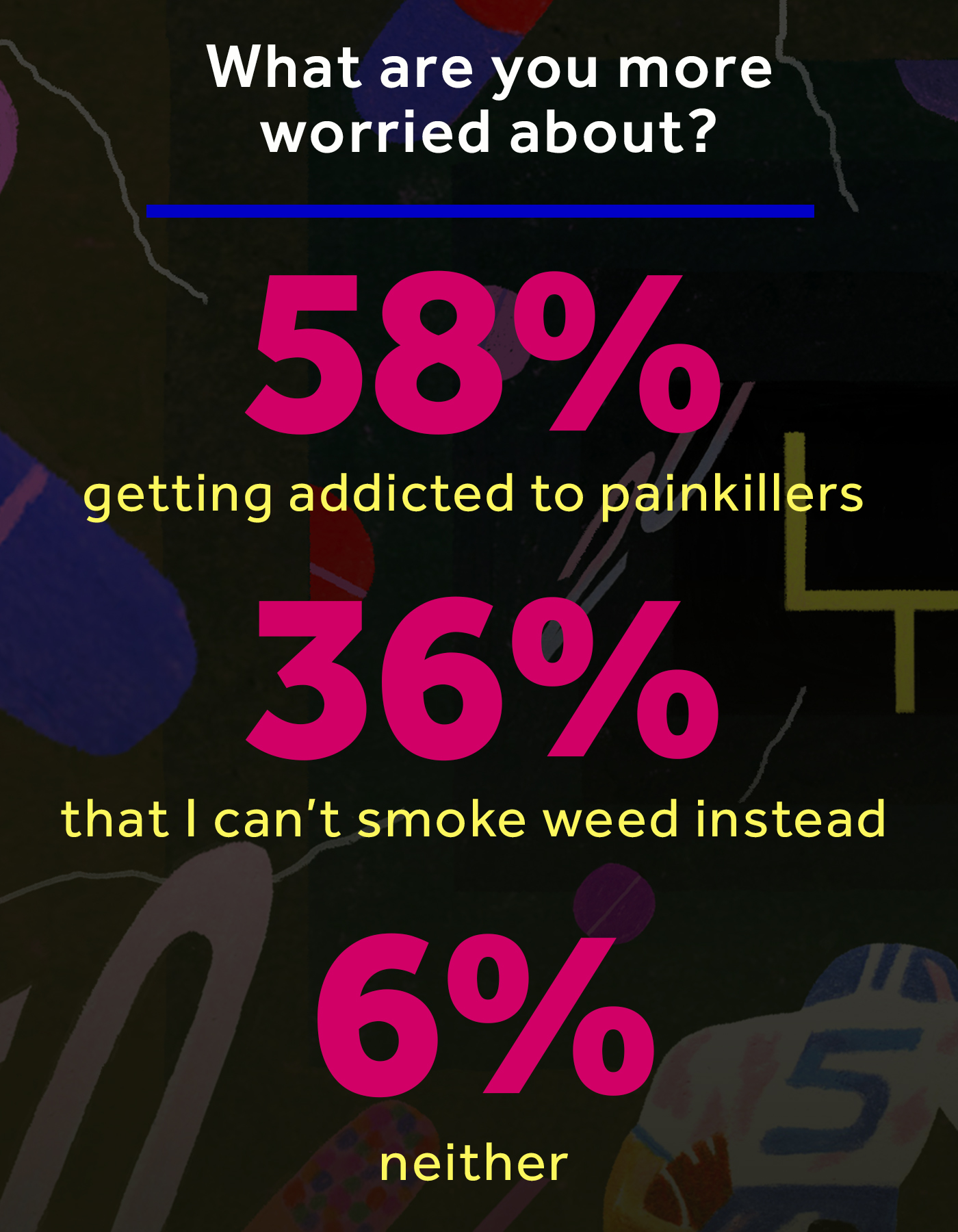

So, "f--k yeah," says one AFC lineman who claims he has seen fellow players get addicted to painkillers. "You'll know when someone gets hurt, they'll be texting or calling: 'You just had surgery. Can I get some Percocets?'"

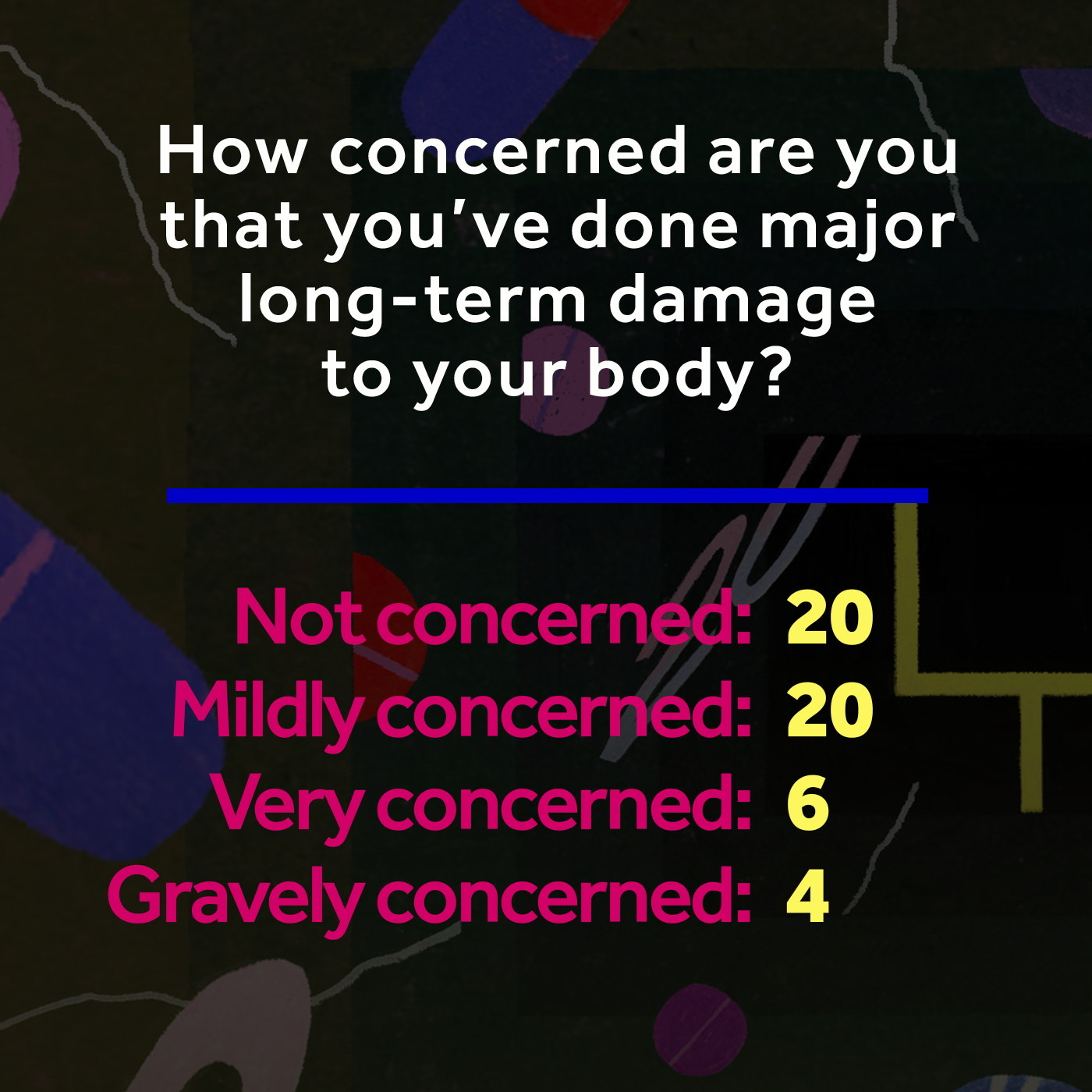

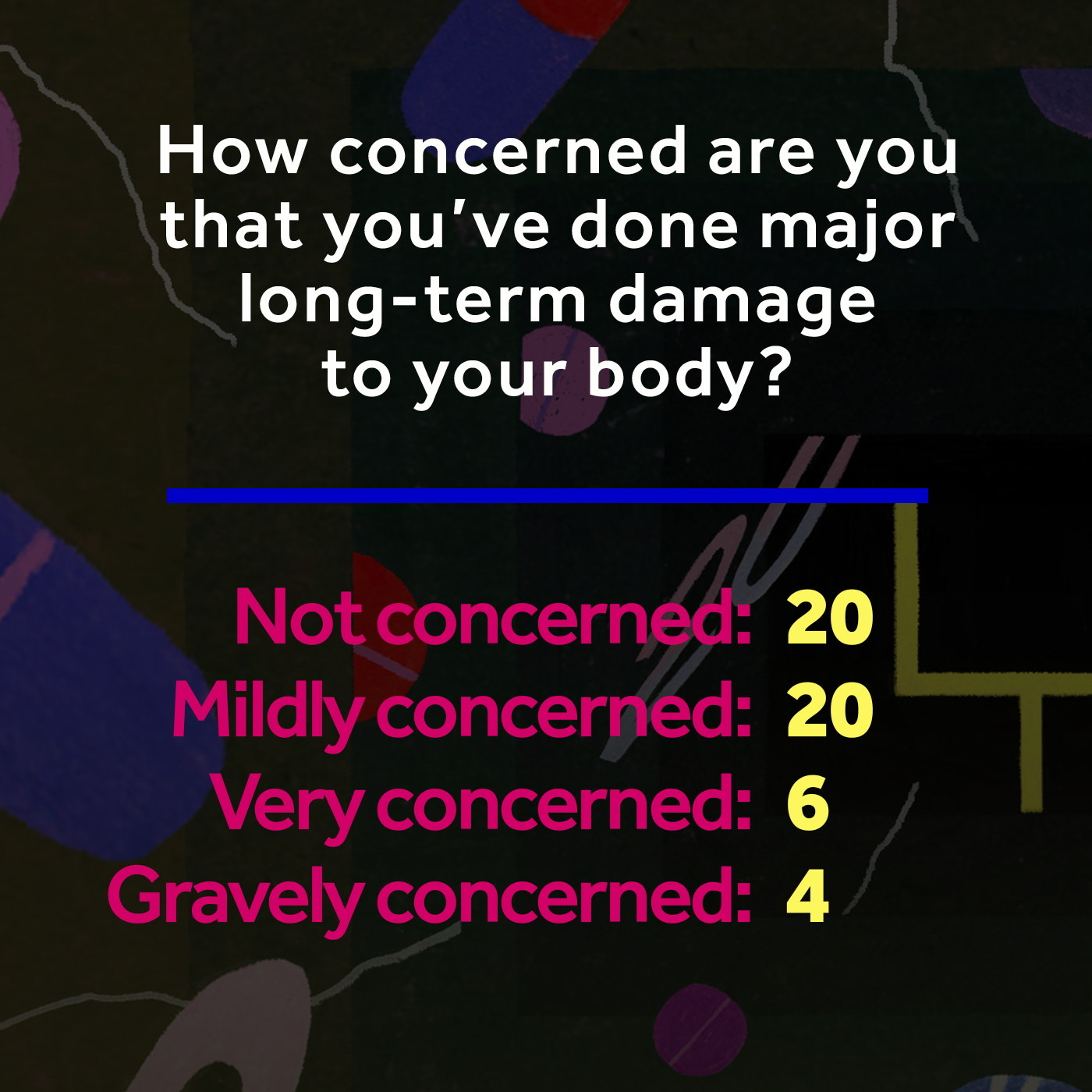

While Toradol helped former NFL quarterback Matt Hasselbeck play through his 160 starts in 17 seasons, concerns that it might make him more susceptible to brain injury gave him pause. At a traumatic brain injury symposium in 2011 with NFL Players Association Executive Director DeMaurice Smith, one doctor said he did not know the long-term effects of Toradol. "They hadn't studied it," Hasselbeck says. Several doctors in the room had a theory: Toradol might put players at greater risk of a concussion because of its blood-thinning properties.

Akin Ayodele (No. 51) hits Matt Hasselbeck during a game at Alltell Stadium on Sept. 11, 2005 in Jacksonville, Florida. (Getty Images)

"And that was the first time I thought, 'If I don't need a Toradol shot, I shouldn't take a Toradol shot,'" says Hasselbeck, who retired after the 2015 season. "That was the only time I felt the need to pump the brakes."

Otherwise, he took Toradol before every game. Hasselbeck suffered broken ribs, a torn MCL, a torn labrum and broken fingers.

"I do wish there was more research going on as far as what they give us and what we're allowed to take," an AFC tight end says. "But I definitely understand the risk that goes with it."

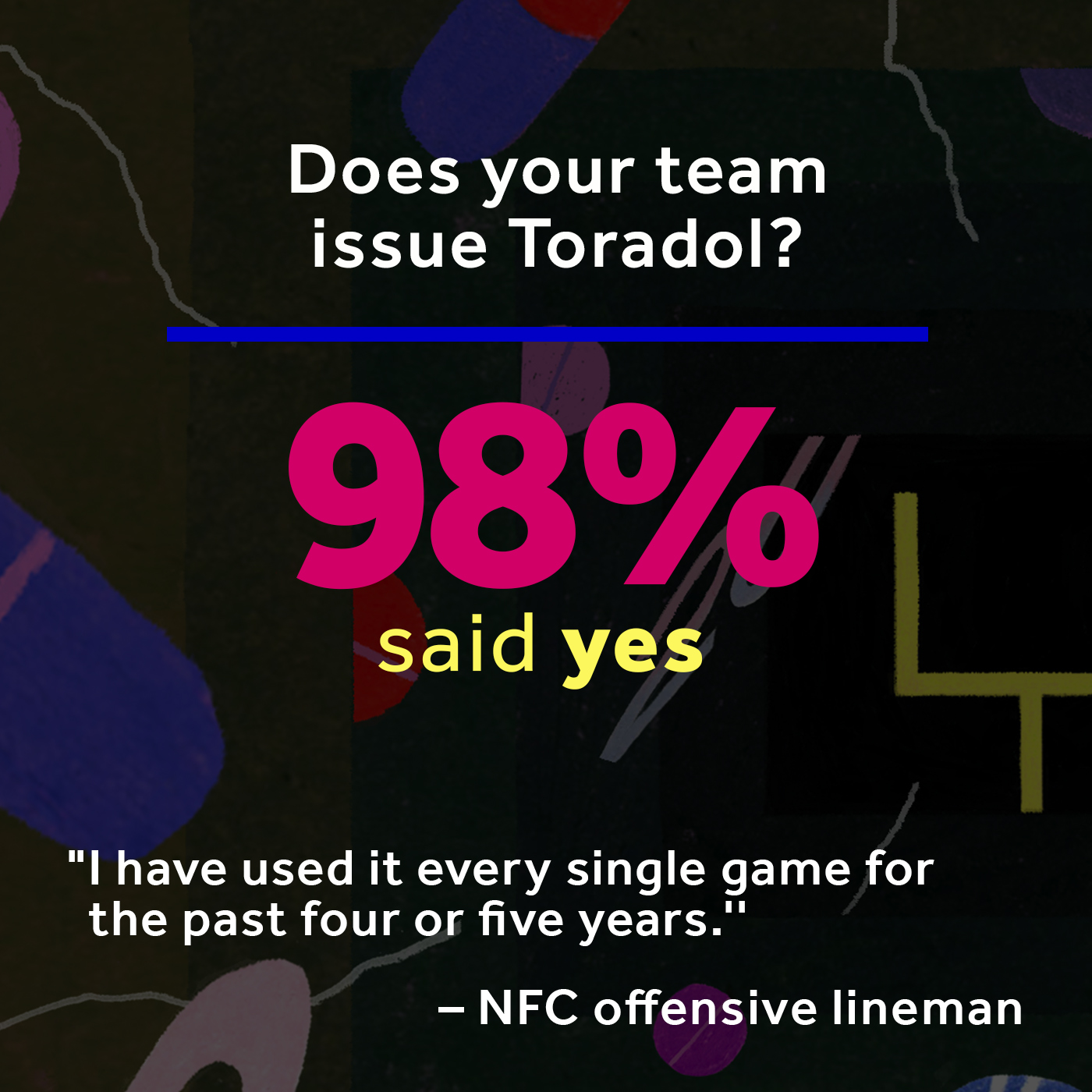

As the NFL told B/R Mag in a statement, Toradol is issued to players on a team-to-team basis; there's no league-wide policy.

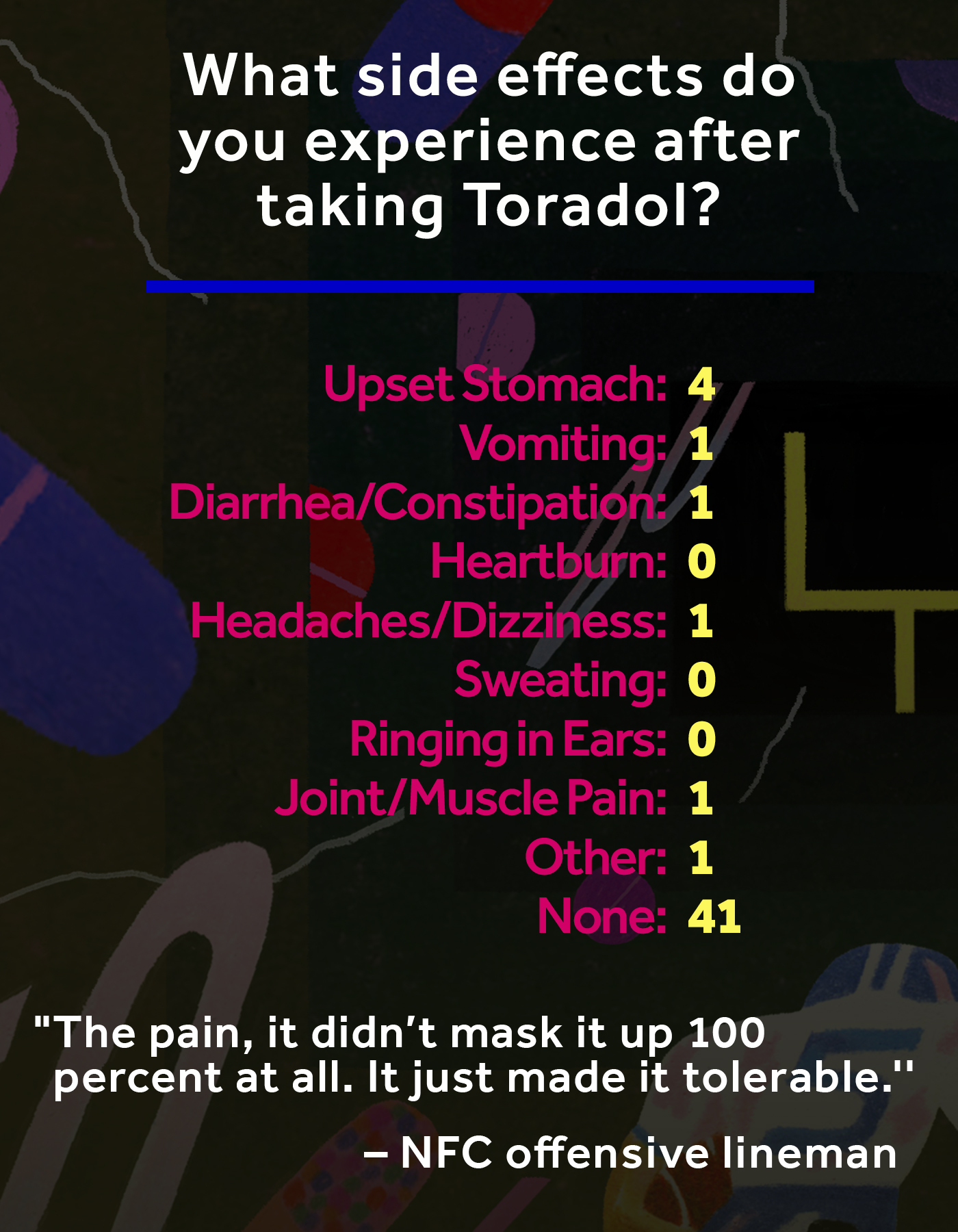

However, the NFL Physicians Society (NFLPS) did release a 2012 paper detailing the effects of Toradol in the journal Sports Health. The study noted that NFL players are "superbly fit and healthy with little risk of experiencing any of the known complications associated with the use of ketorolac," and it offered recommendations for how physicians should deliver it. It said ketorolac should be administered only under the direct supervision (and order) of a team physician, should be limited to players diagnosed with an injury or condition and listed on his team's latest injury report, should be given in its lowest effective dose and not be used in any form for more than five consecutive days.

Further, the NFLPS said ketorolac should be given orally under "typical circumstances," because that has a "faster onset of action" than an injection. According to the study, intramuscular and intravenous injections "should not be used," and ketorolac must not be taken concurrently with other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

As the players explain, the use of waivers and prescriptions for Toradol use varies from team to team.

Many players describe to B/R Mag how NFL teams have banned injections of Toradol entirely, only offering ketorolac in pill form.

"When the team started hearing that some people in the medical field wanted to look at what possible side effects Toradol would have," Hasselbeck says, "they made you sign a waiver all of a sudden. … The young players were like, 'OK, I'll sign the waiver, I just won't take it.' And the older players who had taken Toradol their whole life were like, 'Whoa! Whoa! Whoa! I need Toradol!' So some guys were pushing back. Some guys were begging for it."

The use of Toradol is policed by teams more closely than in the past. Still, Hasselbeck remembers one "powerful-enough player" convincing a team doctor—he would not reveal on which franchise—to give him an injection even though his team had banned it.

Says Hasselbeck, "They were like, 'OK, OK, listen. We'll give you the shot. Just don't say anything. We don't want a line of 20 people in here getting shots. It looks bad.'"

Geier says the Rams handled Toradol responsibly when he worked with the team. One AFC wide receiver suggests to B/R Mag that Toradol was forced upon players—"You think that they have your best interest in mind, which may or may not be true"—but other players say Toradol's popularity is driven by players whose jobs are in constant jeopardy.

"Look at Tony Romo," Geier says of the Dallas Cowboys quarterback who was sidelined this season with a back injury, without suggesting he had taken Toradol. "He lost his starting job and can't get it back. Guys see that. They don't want to miss games. So if Toradol helps them play through pain, that may be something they're willing to try."

So many scientific advancements help players' bodies stay finely tuned—sleep monitoring, massage therapies, hyperbaric oxygen chambers. Geier lists them all. But so often, he says, the question on Sunday remains: What can I do to get through this game?

And yet, 15 other players contacted for the survey say they have never taken Toradol. "From what people say about it," says a Pro Bowl defensive lineman, "it's not something I want to ever deal with." These players emphasize they're wary of putting something into their body that hasn't yet been fully understood. To them, a little extra pain is worth that peace of mind.

For everyone else surveyed, a couple of Toradol pills continue to do the trick.

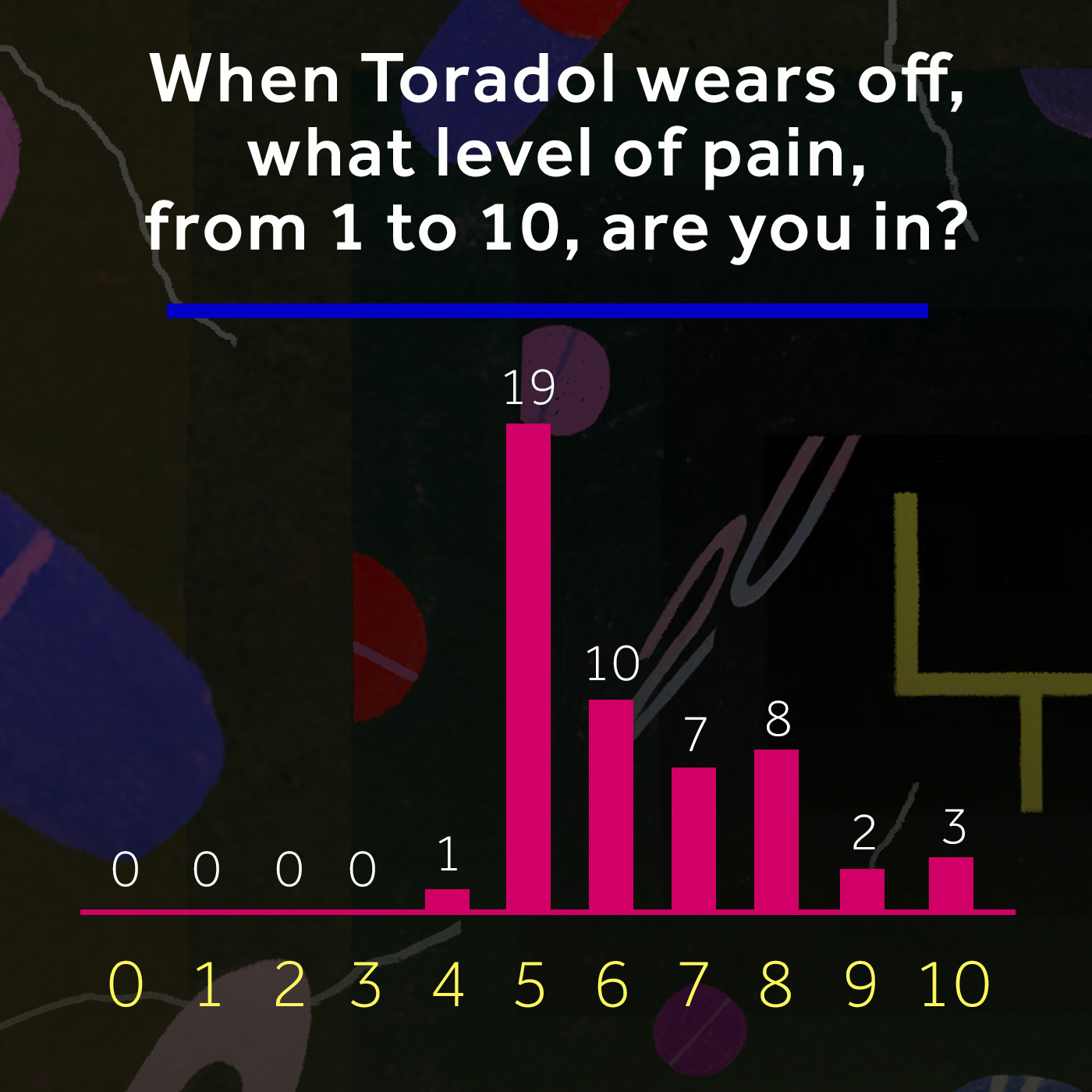

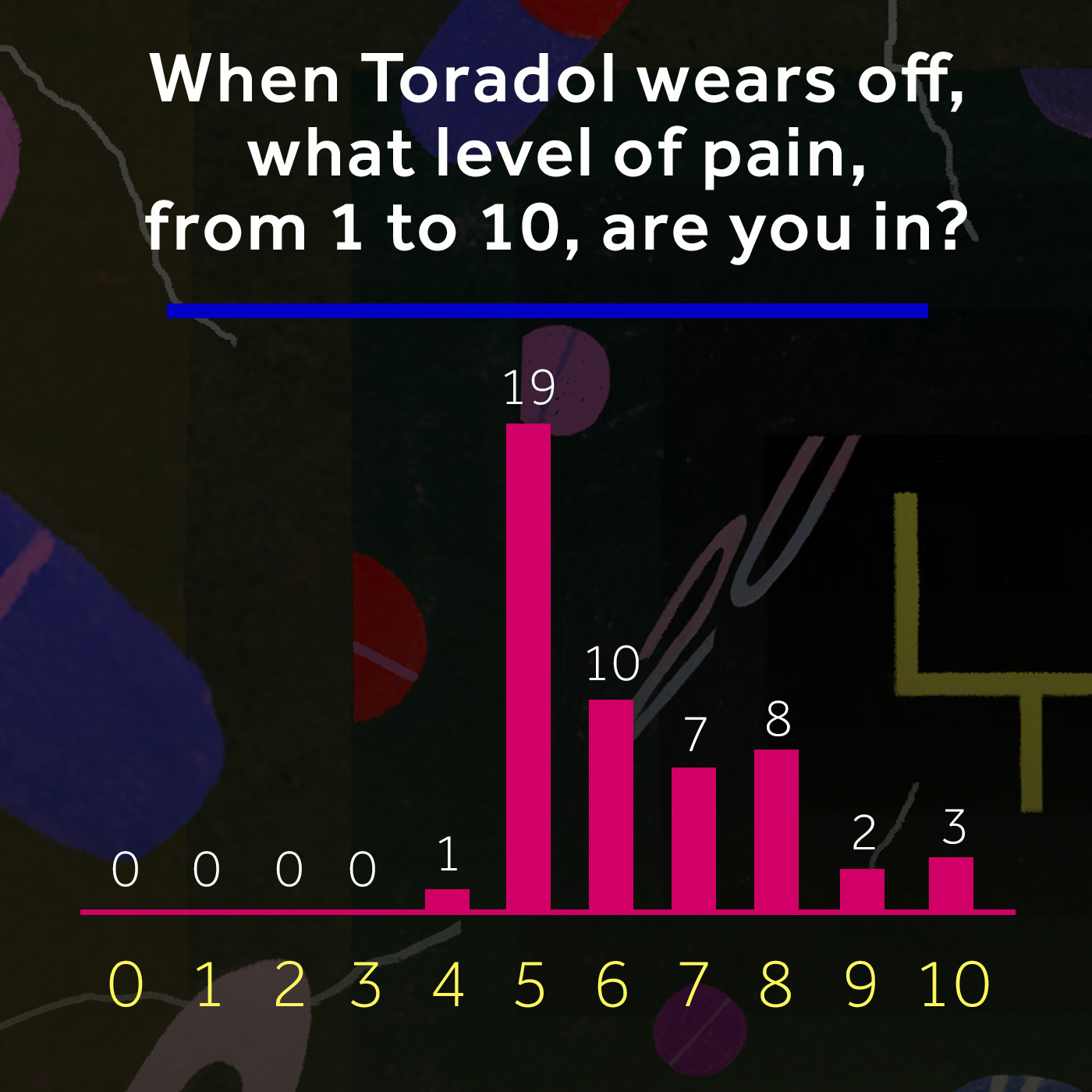

As one NFC safety who describes "shocking" pain on Mondays after Toradol masks his pain on Sundays says, the sacrifice is worth it.

"It gets so bad that Toradol is the only thing that gets you to go," he tells B/R Mag. "So if you're hurting? You're going to have to play. You're going to have to play through it.

"You have to do whatever it takes."