T

he Major League Baseball draft was scheduled for June 2. Two days earlier, John Schuerholz, the Kansas City general manager, received a call from Woods. “Bo would like to visit Kansas City,” the agent said. “He’d like to see the players, see the stadium. But he doesn’t want to work out.”

Schuerholz wasn’t buying it. He suspected Jackson and his agents were merely using the Royals as a negotiating tool against the NFL, and asked Stewart for his opinion. He contacted Gonzales, who assured the director of scouting that Bo Jackson had genuine interest in the major leagues. “John,” Stewart told Schuerholz, “all I can tell you is Kenny Gonzales has spent seven years on Bo Jackson, and he knows him and his family better than anyone. We have to believe in Kenny.”

That Saturday afternoon, Jackson and Woods arrived at Royals Stadium and sat down with Schuerholz, Stewart and Gonzales. The general manager wasted no time. “Bo,” he said, “do you really want to play baseball?”

Jackson was young and green and raw but haltingly sincere and steadfast. “Mr. Schuerholz,” he replied, “that’s why I’m here.”

“OK, OK,” Schuerholz said. Then, nodding toward Stewart and Gonzales, he said, “Why don’t you two take Bo down to meet some of the guys.”

Jackson entered the Kansas City clubhouse, which featured a who’s who of baseball royalty. The Royals were the defending World Series champions—and with good reason. Bret Saberhagen, the ace, was the reigning American League Cy Young Award winner. Dan Quisenberry led the league in saves a record five times. Hal McRae was a three-time All-Star, Frank White a five-time All-Star.

All, however, paled in comparison to George Brett, an iconic superstar and one of the greatest players in the sport’s history. The Royals third baseman greeted Jackson warmly and took time to chat with him about the team. When it was time to leave, Stewart guided the youngster toward the exit when Brett yelled out, “Hey, Bo, good luck in football!”

Jackson whirled around and stormed toward Brett. “Oh my God!” Gonzales yelled—convinced a fight was about to break out. “Bo, don’t…”

He didn’t. Jackson smiled widely, looked Brett in the eyes and said, “George, don’t you bet on it!”

Brett stood, speechless.

Early that Monday morning, Schuerholz barged into Stewart’s office. The draft was to begin in an hour. “Art, Richard Woods called me a few minutes ago,” he said. “He said if Bo plays baseball, he wants it to be for the Kansas City Royals.”

This wasn’t a declaration or a command. Nobody was entirely sure what to do. From a pure talent perspective, Jackson wasn’t simply the top-rated player on Kansas City’s board. He was the highest-graded entry in the draft. But...so what? How is a prospect useful if he doesn’t intend on playing your sport? Was Jackson the future of baseball or an embarrassment waiting to happen? Was Gonzales 100 percent certain he wanted a major league future? Or was there some doubt? A sliver, perhaps?

“The draft is about to begin in a half hour,” Stewart says. “John says to me, ‘Art, you’re the scouting director. I’m leaving this up to you.’”

How is a prospect useful if he doesn’t intend on playing your sport? Was Jackson the future of baseball or an embarrassment waiting to happen?

With the first selection, the Pittsburgh Pirates took Jeff King, an infielder from the University of Arkansas. With the second pick, the Cleveland Indians grabbed Greg Swindell, a pitcher out of the University of Texas. Kansas City held the 24th slot. Names rolled off the board—Kevin Brown to the Rangers, Gary Sheffield to the Brewers, Lee Stevens to the Angels. With the 23rd notch, St. Louis added a second baseman named Luis Alicea. Now, at long last, Kansas City was up.

“I’m in our conference room,” says Stewart. “I have cross-checkers there, special advisers there. I wanted to take Bo. I did. But I was having these second thoughts. Maybe he’d be a superstar. But if he doesn’t sign, we’re all looking for new jobs. There was a lot of pressure.”

When he finally called in the pick to New York, Stewart went not with Jackson but with Tony Clements, a good-field, so-so-hit shortstop from Chino, California, who would never reach the majors.

Thanks to Gonzales’ intel, Stewart knew most of the other teams presumed the Heisman Trophy winner was heading for the NFL. But the Angels scared him. California possessed five picks in the first round and had recently flown Jackson to Anaheim for a meet-and-greet. Among those present that day was Reggie Jackson, the Angels’ cocky slugger and a man Bo Jackson could not have selected from a lineup had he been wearing a "Hello, My Name Is Reggie" nametag. Reggie introduced himself by saying, “You can play football and be the next Jim Brown, or you can play baseball and be the next Reggie Jackson.”

The line went over like expired chicken salad. “I thought maybe he was trying to be funny,” Bo Jackson wrote years later. “He wasn’t.”

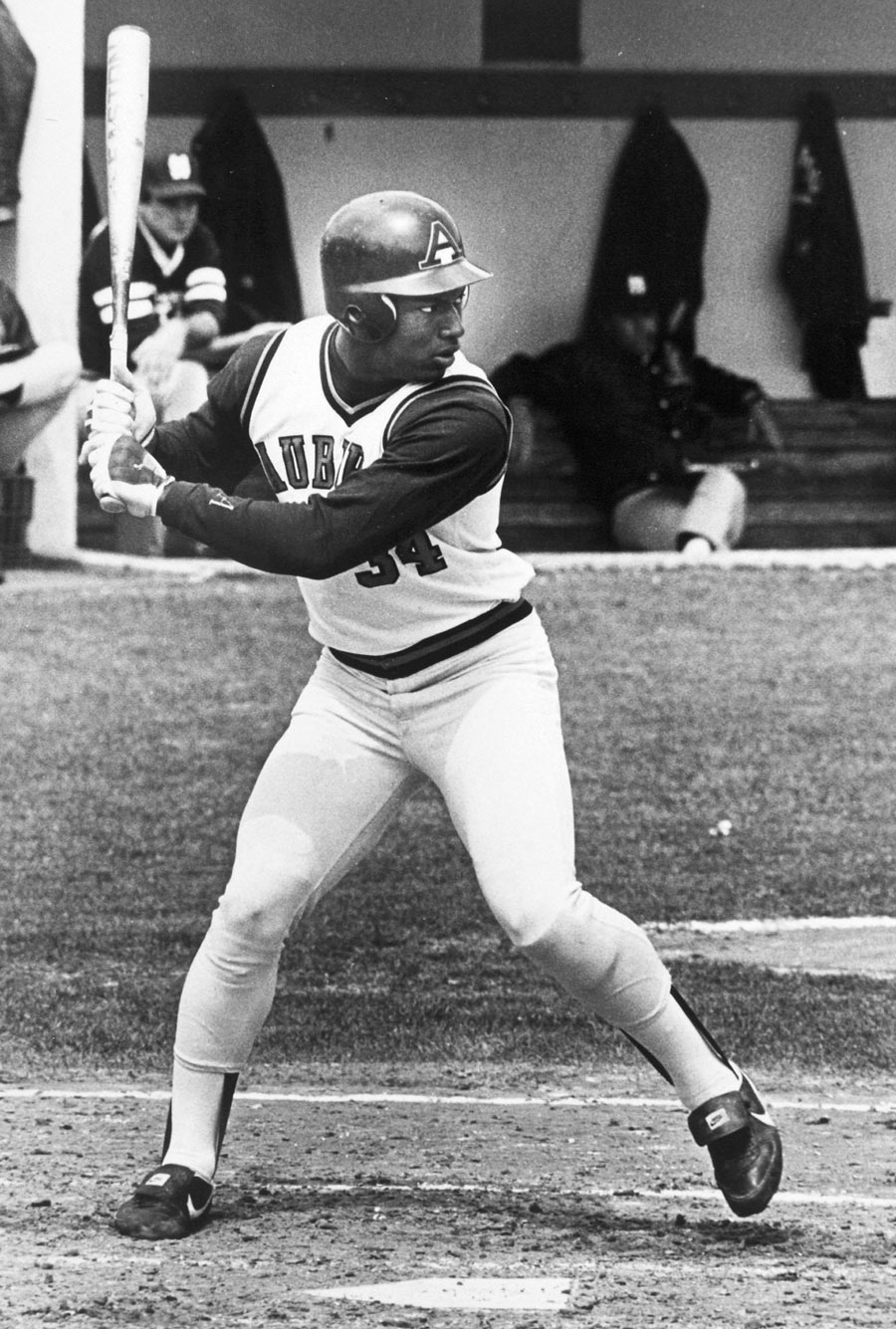

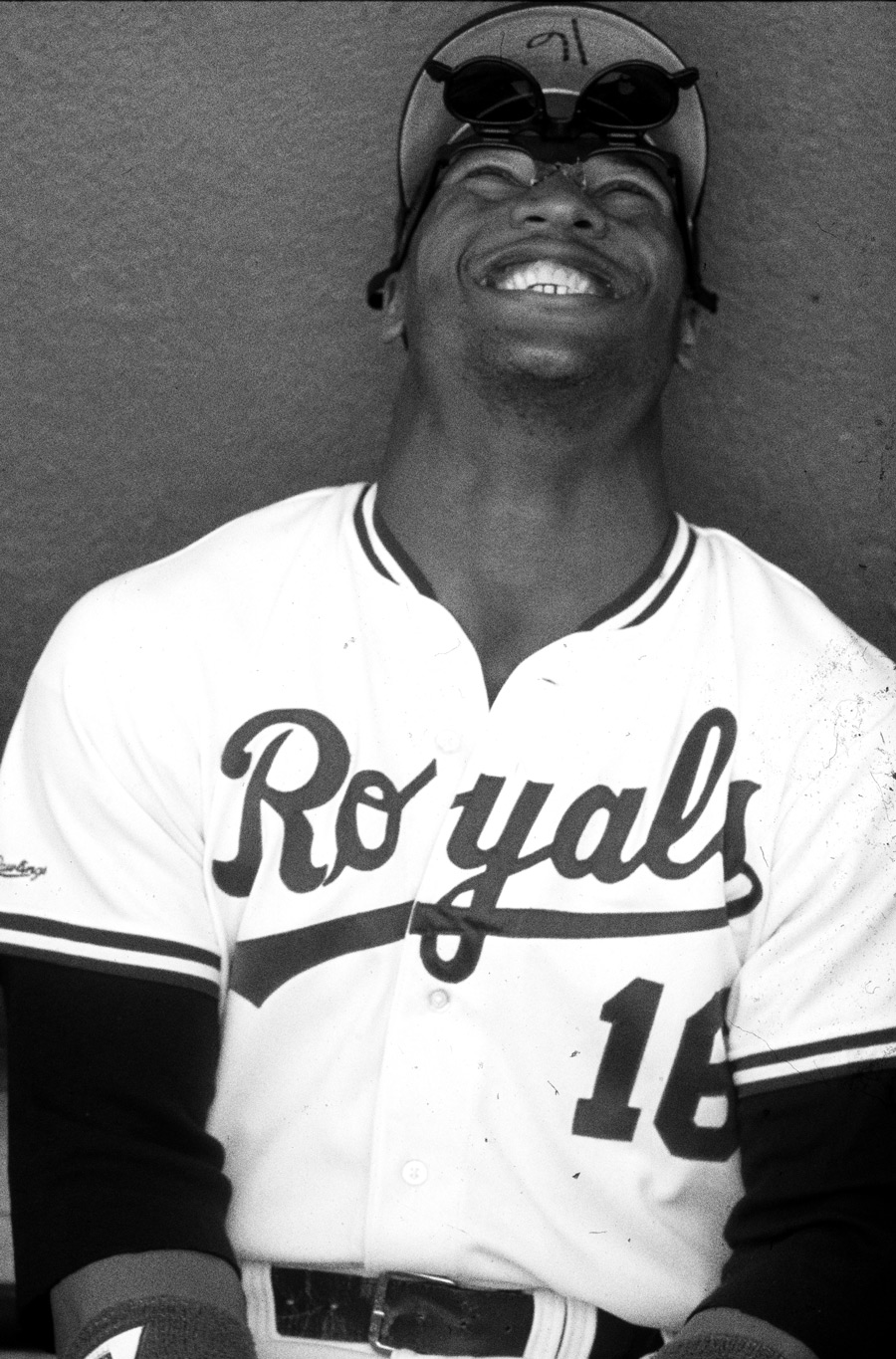

Bo Jackson played for the Kansas City Royals from 1986-1990. (Photo by Ron Vesely/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

L

ike the other franchises, California passed on Jackson, then passed again and again and again and again. Sensing the mass trepidation, Stewart held off, too. Finally the fourth round arrived. No. 4 was the scouting director’s lucky number. He wore the digit during his amateur playing days. In 1970, during his first draft with the Royals, he used a fourth-round pick to take Tom Poquette, an outfielder who enjoyed a solid big league career.

“I’m not overly superstitious,” Stewart says. “But I always felt good about four, and now I was thinking, ‘We can get one of the greatest athletes who ever lived, with a super-high ceiling, and even if he never plays for us, the fourth round isn’t a ridiculous risk.’”

The decision was made. Stewart dialed the number for the major league draft headquarters and said, with quiet confidence, “The Kansas City Royals select Vincent Edward (Bo) Jackson from Auburn University.”

“There was silence at the other end,” he says. “It was a moment.”

Three weeks later, on June 21, 1986, Jackson returned to Royals Stadium to meet with reporters and announce his new post-collegiate profession. He held up a white Kansas City jersey, wore a blue KC cap and smiled like a man whose future was secure. His contract ($1 million over three years) wouldn’t touch the Tampa money, but Jackson couldn't care less.

“You can play football and be the next Jim Brown, or you can play baseball and be the next Reggie Jackson.”

- Reggie Jackson

“I went with what is in my heart,” he said. “My first love is baseball, and it has always been a dream of mine to be a major league player.”

Standing to the side, beaming from ear to ear, Florence Bond could not contain her euphoria. After all those years of struggle, her family was, at long last, on the rise. She listened intently to her son’s words, and when the press conference ended, she found the one man in the room who stuck with her through highs and lows, hope and helplessness, faith and fatigue.

“Kenny!” she screamed—and hugged the most loyal customer the Hoover Ramada Inn had ever known.

The two embraced for what felt like days, and both knew Bo Jackson had made the right choice.

Professional sports was about to welcome a revolutionary athlete. One year later, Jackson would officially sign as a part-time running back with the Los Angeles Raiders, citing his desire to pick up an extra "hobby." But he was always, first and foremost, a baseball player.

“And it all came down to one thing,” says Stewart, now 89. “The patience and skill of a great scout.” ◼